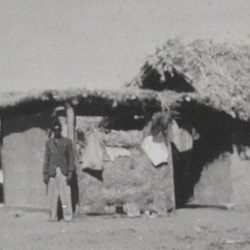

Marrngu lived and worked in shifting mining camps set up across a wide area of the Pilbara, with both men and women engaging in mining.

Men Mining at Gorge Creek

Citation

Photo by John Wilson.

The Western Australian Government’s cautious support for the movement gave rise to conflict with pastoralists, who were used to having their labour needs prioritised by the Department of Native Affairs.

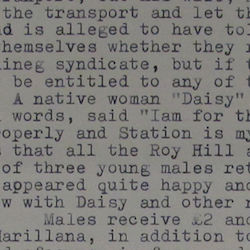

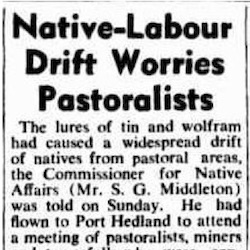

Native-Labour Drift Worries Pastoralists

Citation

West Australian, 22 August 1951, p. 2, ‘Native-Labour Drift Worries Pastoralists.’

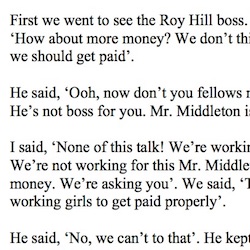

Among those who left stations at this time was a dynamic woman called Daisy Bindi, who led almost a hundred people into the cooperative from Roy Hill station in early 1952, after their negotiations with station management had failed to achieve the improvements in wages and conditions they were seeking.

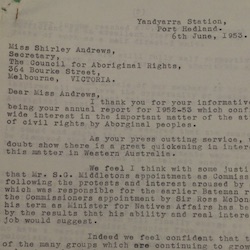

Daisy Bindi Leads People from Roy Hill Station

Citation

South Australian Museum, AA346-4-22-1 Pilgangoora R514.

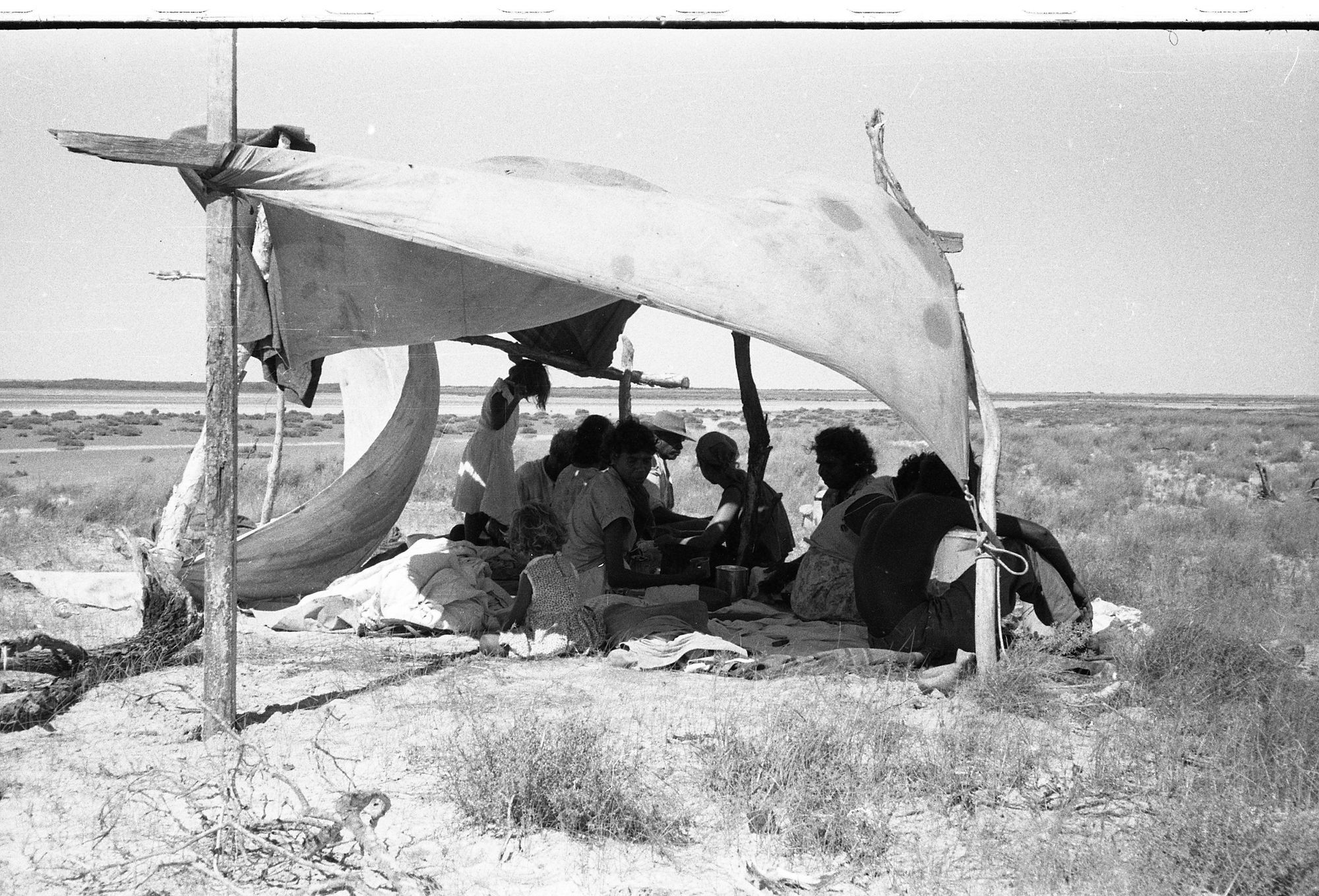

An effective social organisation was established, with systems for decision-making and dispute resolution. The organisation had to work as an economic unit as well as being socially and culturally satisfying to its members. Camp committees and women’s committees were established. Yandeyarra was run by Peter Coppin and a women’s committee, photographed in October 1953 by Bill Rourke.

Committee Women and Peter Coppin at Yandeyarra

Citation

State Library of Western Australia, from a collection of photographs used by W.H. Rourke in his book My Way, BA729 (Albums).

Sam Fullbrook built a studio at the cooperative’s mining camp at Pilgangoora Bore, and recorded his experiences in paintings.

Pilbara Painting

Citation

Pilbara painting by Sam Fullbrook.

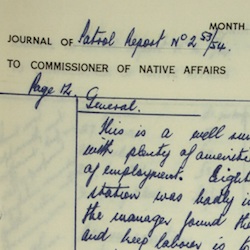

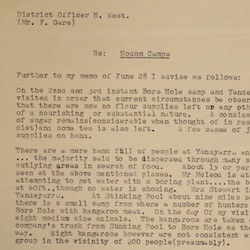

The Department of Education’s Inspector of Education also strongly recommended that a school be established at Yandeyarra. However, the financial collapse of NODOM in 1954 led to the Department abandoning this plan, to the great disappointment of the community.

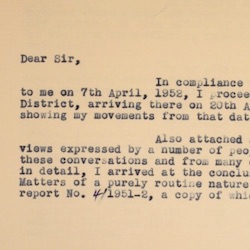

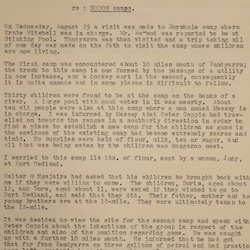

Department of Education Report on Visit to Yandeyarra Station

Citation

William H. Rourke, Report on Visit to Yandeyarra Station, 3 November 1953, SROWA, 1952/0535/22-26.

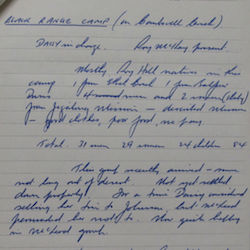

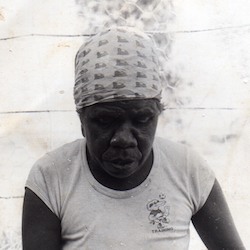

When NODOM went into liquidation, the group was unable to market its minerals or buy food. Many marrngu left the group. Some remained, however, surviving through what became known as the starvation time. This is remembered by Munda Woodman, who was a child at the time. Munda Woodman and Ron (Rinti) Hale were children attending school at Yandeyarra in 1953. Children were cared for by Massey Chillawarra and his wife Lily, who took children to a remote pool to live off the land.

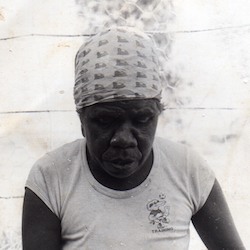

Munda Woodman and Ron Hale, Starvation Time

Munda: Starting school then, Massey and his old wife, they were the boss for us, and all the boys [Munda is unable to say the name of her classificatory son-in-law, and asks her husband Ron Hale (Rindy) to say the name].

Ron: Paddy Yaparla

Munda: Mm. He’s the boss for the boys, big boys. Then we starting bit of school, you know, we starting.

Ron: Max Brown, his wife, Kathy.

Munda: Kathy Brown. Max Brown and Kathy. That’s one of his wife.

Ron: Then we went, we bin biggest starvation then.

Munda: Yeah, we bin starvation for tucker that time.

Ron: We split up, finish school

Munda: Then we split up. Massey took us down to the Elephant Camp. Elephant camp, from Yandeyarra. That river called Elephant Camp. We were staying out there then. We had no flour, no sugar, no tea, we used to hunt for honey. Old people would hunt for honey, put it in the water, mix it with the water, make it sweet. Live on kangaroo, just water. Then after later one of them Welfare blokes was helping us with food then. We bin just starving for I don’t know how long, three or four months, I think. That welfare bloke was helping us then, bringing the food for us, you know, flour and sugar. Harvey Tilbrook or one of them Welfare blokes. Help us for food, you know. Bring a little bit of food for the old — for the old people and kids.

Citation

Audio: Munda Woodman and Ron Hale (Rinti), recorded by Anne Scrimgeour, Mijijimaya, 26 June 1993, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library.

Photo: Munda Woodman, Mijijimaya c. 1990, Anne Scrimgeour.

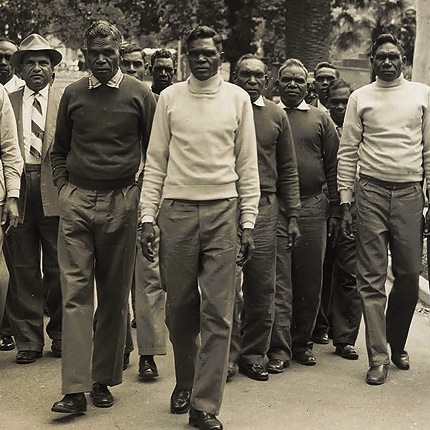

This photograph shows Mitchell, Middleton and other members of the group with a truck that was purchased by the Department for the Pilbara Native Society. Middleton’s willingness to assist marrngu as a group rather than on an individual or nuclear family basis is a measure of the authority they had established. The Department went to considerable cost, purchasing not only this vehicle but mining equipment and Riverdale Station for the Society.

Department Purchases Vehicle for Pilbara Native Society

Citation

Pilbara Native Society group photo, State Library of Western Australia, BA368/6.

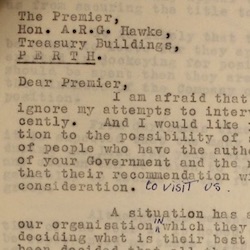

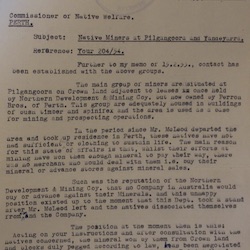

Marrngu initially elected to work with both men, but Middleton refused to involve his department in any arrangement that included McLeod. This account of the events, written by McLeod and distributed on the Fremantle waterfront, has been annotated by Middleton, who underlined in red any statement he considered false or incorrect.

McLeod Statement on Struggle to Manage Group's Affairs

Citation

Don McLeod, Statement, 29 May 1955, annotated by Stan Middleton, SROWA, 1954/0204/91-96.

The group and the government had established a good working relationship in the early years of the 1950s, but this relationship deteriorated badly in the latter half of the decade. This photograph shows Pindan men in Perth to attend court for a libel case they took against the Australian Broadcasting Commission and Commissioner for Native Welfare Middleton.

Pindan Men in Perth for Libel Case

Citation

Photo from West Australian, 20 October 1958.

Autonomy and self-reliance remained a keynote of the group’s ideals.

Pearl Shelling Camp

Citation

Pindan shelling camp, photo by John Wilson.

Pindan continued to work in mining and eventually regained Yandeyarra station. This is a photograph of Pindan’s shareholders, including Ernie Mitchell and his wife, Lucy, on the right.

Pindan Shareholders

Citation

Photo by John Wilson.

In the 1950s the men and women who had engaged in the strike became less concerned about employment conditions on stations and focused instead on establishing themselves as a socially and economically independent community. They engaged principally and most successfully in mining, but also in seed collection and dry-shelling. For a time, they enjoyed remarkable financial success and prosperity, and at other times they endured hardship and poverty. Their relationship with government also fluctuated, from good-will and cooperation in some years, to opposition and conflict in others. At one point, 700 people, most of the Aboriginal population of the region, were involved in the movement; at other times numbers dropped below 200. What they achieved throughout these shifts in fortune was the right to exist and make decisions as a group, to have their authority as a group respected by others, to select their own leaders and representatives, and to live their lives with dignity and in accordance with Aboriginal cultural beliefs.

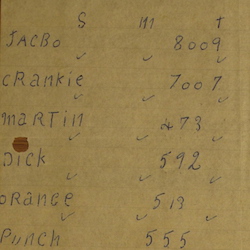

Mining

The mining cooperative began in the later months of 1949 when some of the strikers began prospecting with Don McLeod. His knowledge of minerals and markets, together with the extensive knowledge of country and highly-developed powers of observation of the Aboriginal prospectors, were to be a recipe for the success of this venture. The group made significant and valuable discoveries of columbite and wolfram, which were extracted using hand tools and separated with the use of the yandy. Their success attracted increasing numbers of people to the community in the early 1950s. No-one received wages, but profits were used to buy food, clothing and equipment, and purchase and run vehicles.

Men Mining at Gorge Creek

Marrngu lived and worked in shifting mining camps set up across a wide area of the Pilbara, with both men and women engaging in mining.

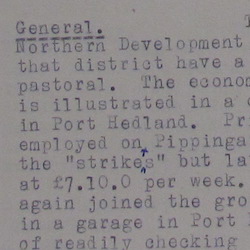

Native-Labour Drift Worries Pastoralists

A cooperative mining company, Northern Development and Mining (or NODOM) was established at the end of 1951. The success of the mining venture led the government to withdraw its opposition to the movement. By 1952, upward of 700 people were involved in the independent mining community, and the local pastoral industry was facing even greater labour shortage than during the strike. As a result, a Committee of Inquiry was appointed by the government to investigate the circumstances in which marrngu were leaving the stations.

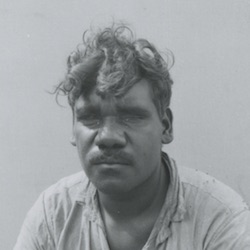

Daisy Bindi Leads People from Roy Hill Station

Among those who left stations at this time was a dynamic woman called Daisy Bindi, who led almost a hundred people into the cooperative from Roy Hill station in early 1952, after their negotiations with station management had failed to achieve the improvements in wages and conditions they were seeking.

Autonomy

Organisational structures that had been established during the strike were developed, adjusted and refined during the early 1950s. Aboriginal law and social and cultural practices formed the basic framework, but new structures were developed within this framework to meet the needs of a mining company. It was an organisation that had to work as an economic enterprise but also satisfy the social and cultural needs of its members. The group adopted democratic principles, with decisions made through discussion and consensus. New structures were trialled and adopted or rejected. Violence was outlawed, and an alternative system of dispute resolution was established. The principal leader of the group at this time was Ernie Mitchell.

Committee Women and Peter Coppin at Yandeyarra

Obtaining land had been a primary objective of the strike and this was achieved with the purchase of Yandeyarra station from the profits the group had made from mining. Government approval of the movement provided de facto recognition of the right for Aboriginal people to control their own affairs.

Pilbara Painting

Idealistic men and women, including writers and artists, travelled to the Pilbara from other parts of Australia, to be a part of this exciting social experiment. They included the artist Sam Fullbrook who built himself a studio at the Group’s tanto-Columbite camp at the Pilgangoora Bore. At a time when Aboriginal administrations across Australia were planning policy for the incorporation of Aboriginal people into mainstream Australian society, these men and women were, to some extent at least, being incorporated into an Aboriginal social organisation.

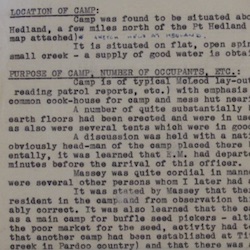

Department of Education Report on Visit to Yandeyarra Station

Education was a major objective of the group. Most had had no formal schooling, and they saw literacy as vital if they were to achieve full independence. This Western Australian Department of Education report documents the community’s strong desire for a school and strongly recommends that one be provided.

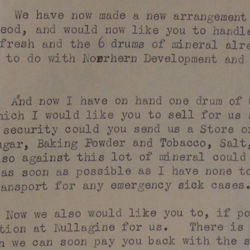

Financial Collapse

Although the group made large profits in the early 1950s, earning about £50,000 in 1951 (equivalent to $2 million today), its company, NODOM, was facing bankruptcy by the end of 1953. By the second half of 1954 the group was facing starvation. McLeod shifted to Perth, engaging in legal disputes over NODOM’s assets and attempting to raise funds. In early 1955 Mitchell applied to the Department of Native Welfare (as the Department of Native Affairs was now called) for urgent assistance. In response and on the understanding that McLeod was no longer involved, the Commissioner for Native Welfare, Stanley Guise Middleton, established the Pilbara Native Society to replace NODOM, with arrangements for local departmental officers to market minerals for the group.

Munda Woodman and Ron Hale, Starvation Time

When NODOM went into liquidation, the group was unable to market its minerals or buy food. Many marrngu left the group. Some remained, however, surviving through what became known as the starvation time. This is remembered by Munda Woodman, who was a child at the time.

Department Purchases Vehicle for Pilbara Native Society

This photograph shows Mitchell, Middleton and other members of the group with a truck that was purchased by the Department for the Pilbara Native Society. Middleton’s willingness to assist marrngu as a group rather than on an individual or nuclear family basis is a measure of the authority they had established. The Department went to considerable cost, purchasing not only this vehicle but mining equipment and Riverdale Station for the Society.

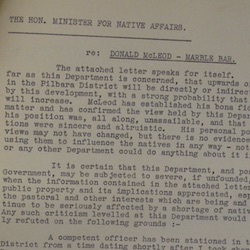

McLeod Statement on Struggle to Manage Group's Affairs

While Middleton was setting up the Pilbara Native Society, McLeod was in Perth arranging for the establishment of another company, called Pindan Pty Ltd, to replace NODOM. When McLeod returned to the Pilbara in May 1955, after nine months’ absence, Middleton rushed north to persuade marrngu to stick with the Pilbara Native Society. At a historic meeting at the Bore Camp, Middleton and McLeod vied with one another for the right to manage the group’s affairs.

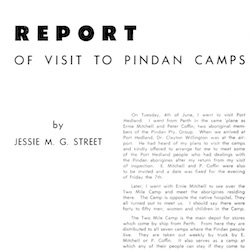

Pindan

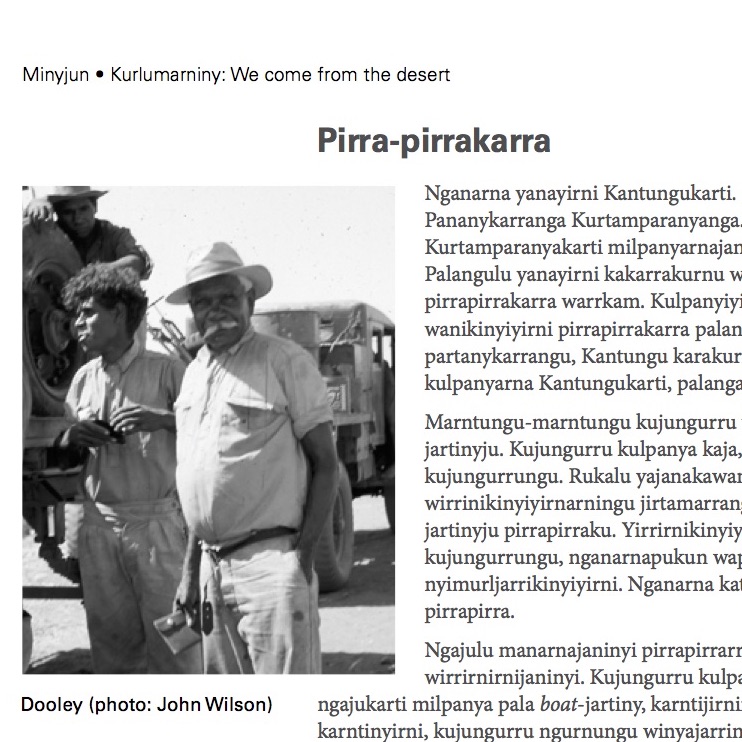

The group’s decision to have their business affairs managed by McLeod rather than the Department of Native Welfare led to the formation of Pindan Pty Ltd. Mitchell, as shareholder and one of Pindan’s Directors, retained leadership of the group. In 1956 and 1957 Pindan shifted away from mining to pearl-shelling and seed gathering along the Pilbara coast.

Pindan Men in Perth for Libel Case

The group and the government had established a good working relationship in the early years of the 1950s, but this relationship deteriorated badly in the latter half of the decade. This photograph shows Pindan men in Perth to attend court for a libel case they took against the Australian Broadcasting Commission and Commissioner for Native Welfare Middleton.

Pearl Shelling Camp

Autonomy and self-reliance remained a keynote of the group’s ideals.

Pindan Shareholders

In 1958 Pindan returned to mining, embarking on a joint manganese mining project with Albert Sims and Co, through a syndicate company called Simdan. However, discontent within Pindan led to upheaval in the company’s affairs and to McLeod’s resignation in 1959. Pindan became a wholly Aboriginal company. This photograph of the Pindan shareholders with their wives was taken by the anthropologist John Wilson.