Snowy Jittermarra recalls the resentment felt by marrngu over the way they were turned out of the stations during the slack period, in just the same way that horses were turned out into a paddock. These and other grievances were discussed with McLeod.

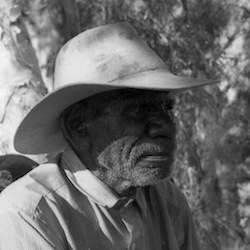

Snowy Jittermarra, Looking For A Way

I just growing up now, and all the old people bin make up their mind, ‘How we going to help ourself do the–, can't see’m self nobody, no help from the white fella’. They say to themselves, ‘O, why don't we talk about something?’ They start to wait for everybody, we start talk about something. Anyhow they did talk about what to do. We're working, everybody working, and nothing - they know something about money now, they’re learning. Alright, some working ten bob a week, and some working two bob, five bob, keep going like that. When they going for a holiday they give them all the silver, five bob, fifty cents, five bob or two bob, plenty two bob, plenty five bob. And when we going for [pingkayi], when we going from the stations for a holiday now they turn him out, turn us down just like a horse, when we take the shoe turn him put him all in the good paddock, and the same time we got to walk out from the station, walk back to Nullagine, or somewhere else. Lot of station like that, Roy Hill, between Roy Hill and Noreena station there’s a meeting ground there belong to everybody. We used to come to that meeting. Anyhow when the time come, sometime we might running late, well we see the policeman coming. ‘Hey, there's a policeman coming’. All the boys there, how many people belong to the Noreena or Bonney Downs, he sort them out, police got to sort them out. And when you ready to go, you better go in the time. Sometime we running late little bit, maybe just about another couple of weeks or three of four days or–, running little bit late. Well we see the policeman coming, push us back to the station. And we got to walk back, we got to walk out from the station, to some sort of place might Nullagine, from Noreena to Nullagine. We got to walk from there. When the policeman come well we got to walk back to station. And squatter was oh, happy, ‘Oh, you come back?’ Never say anything. Next day, never going to give us spell, just after we bin walk from Nullagine to Noreena and we got to start straight away. We might get there about afternoon, in the morning we going to start work, doesn't matter how tired. And that's the way we are.

Alright, all the old people put together, and mention about this Don McLeod. ‘Hey, Don McLeod is a good man. Can we try that man give him a talking up?’

‘Mmm, alright’.

My father was talking to everybody now, and we start. Some, two or three fellas bin working, my father's brothers, all the brothers anyhow, bin working with the Don McLeod, good well sinker, sinking well, all around Noreena boundary and Nullagine, they was making that– put up the windmill there. They keep talking. ‘Can you help us? No good we camping in the rubbish heap, we're camping in the river, when the rain come we got to run back to shearing shed, we got to camp amongst the sheep when it's shearing time, you know? We got to camp amongst the [sheep]. Some camp in the saddle room, some camp in the shearing shed, some old people they still in the river, putting some sort of iron or canvas, just enough to keep him bit dry but still they get wet through’.

Alright, all that problem now, we start working on that one now. Alright, and Don McLeod say, ‘By God, we're going to be in trouble’.

‘Oh well, we're all going to be in trouble, we'll help you and we'll stick together and help you’.

‘Alright’.

He did.

Citation

Audio: Snowy Jittermarra, recorded by Anne Scrimgeour, Warralong, 5 August 1993.

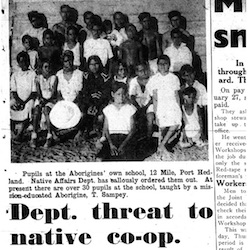

Photo: Board of Anthropological Research, South Australian Museum, AA346/4/22/1 Marble Bar R352.

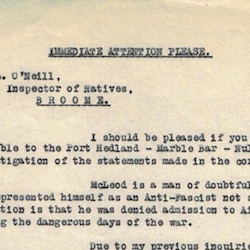

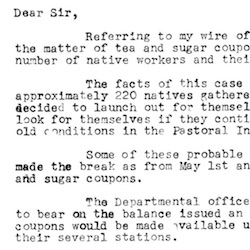

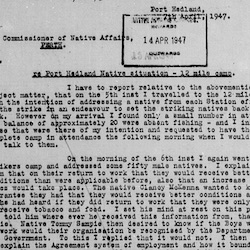

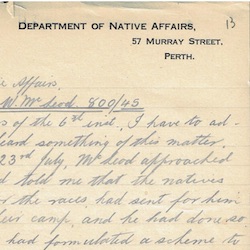

Ideas discussed included a scheme to obtain land of their own and set up economic enterprises so they would no longer be dependent on station employment. In 1945 marrngu from across the region held meetings to discuss these ideas when they converged on Port Hedland for the annual horse races. Constable Les Fletcher of the Port Hedland police was invited to attend. This is his report of the meeting.

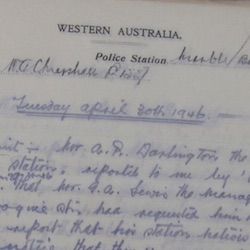

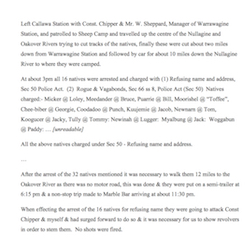

Constable Fletcher's Report on Race-Time Meetings

Citation

Constable Les Fletcher to Francis Bray, 10 August 1945, SROWA, 1945/0800/13-17.

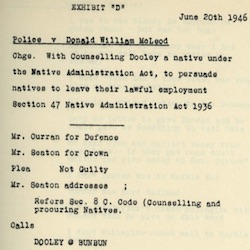

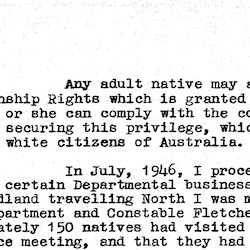

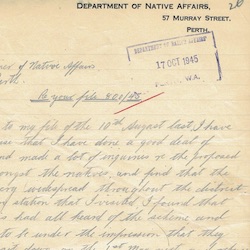

The Aboriginal organisers travelled around the area spreading the word about the strike. The Department of Native Affairs was troubled by this and tried to counter it. Nyamal man, Clancy McKenna, was one of the principal organisers. Dooley Binbin, a Nyangumarta man, took up an organising role late in 1945.

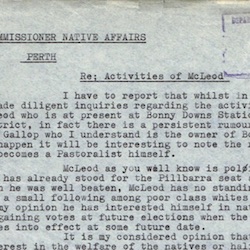

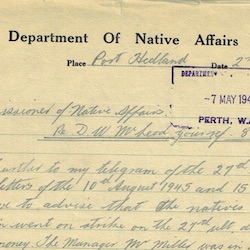

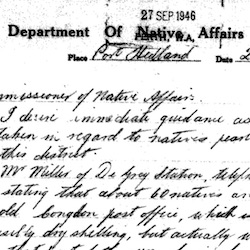

DNA Attempts to Stop Aboriginal Organisers Spreading the Word

Citation

Les Fletcher to Francis Bray, 15 October 1945, SROWA, 1945/0800/26-29.

Small communities of marrngu on widely dispersed stations found it difficult to conduct a strike of this nature. Kujupurra (Cranky) was a cattleman on Warrawagine station on 1 May 1946. He recalls the tactics used by the police to suppress the initial strike action.

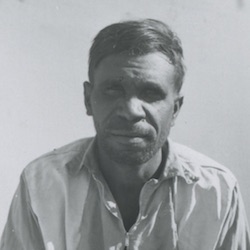

Cranky Iti, Striking at Warrawagine Station

Palanga waninyiyirni pala now yinyapulunganinyi mirlimirli, mirlimirli yinyapulunganinya strike-jarrinyaku. Waninyirni warrkamjarrinyiyirni, number pala day, karrpu pala scratch’m-jinikinyiyirni yamanikinyiyirni. Palaljinikinyiyirni palaljirniyirni. Pulukukarrapa ngurnungu jalpu again, kukurnjari mapulu, nganarna purlikapurluku jalpu again, Bill Sheppard nyampalilu kanganyinganinyi. Ngurnungu karajirri Pintunyanga mirtalu mirtapulkarralu kanganyikinyijaninyi marrngujakun jana. Nganarna whitefella-lu kanganyikinyinganinyi kanyayirni, warrkamjirniyirni purlpi wangkajarrikinyi Braeside-ja, kulpanyakawanikinyiyirni pulukujartiny Warrawagine-karti. Warrawagine-jarrinyiyirni finish. Palanga kalkunikinyiyirnijaninyi puluku puru ngarra home paddock-ngi kanka winya wanikinyinganarnaka. Nyungu janalu kukurnjari yartanga puru kanka again wanikinyijanaka. Yana palanga kuwarringi kuwarringi nyarra, finish. Kuwarringi.

“Ngapijarruluminyi ngurranga, ngurranga wantuluminyi, muwarrpiliminyalu,” wurrarnirna.

“Yu” karramarnayirni everybody.

Ngurnungu karajirri self again muwarrpirniyi.

Yarlipala turlpanyiyirni. Munu yanamayiyirni yawartakartipa. Warliyirninganinyi yawartaku, munu parrjalkulinypa yarta. Yanayirni meathouse, garage, meathouse pala wanikinyi, palanga all the time camping raintime-pa. Palangarra wanikinyiyirni, puralypartu nganayirni, puralypatukarti yanayirni, stockyard ngurnungu, Cattle Camp palanga nganayirni puralypatu.

Marrngulujakun palaja pipurru yanayirni mayakarti. Mayakarti yanayirnijanaku. Tulpanyapulunganaku ngapi, Jim Lewis, he’s the manager, and overseer Billy Sheppard. Palajirri stockmen nganarnamili wurrarniyirni, tulpanyanganaku, “Anybody got a horse in the yard?”

We said, “No, nobody went to get the horses”.

“Ah, what’s wrong?”

“Well, this day we’re finishing off”.

That was 1946.

“Ah, what give you fellas hand? Somebody give you fellas hand?”

“No. We just make up our minds to stop, because we got no home, we camp in the river...”

“Ah, yeah? Might somebody give you a hand?”

“No, we just make up our mind because we get low wages and rubbish tucker, tucker in the woodheap”. Jipi.

Pala finish. “Well, you wait, I’ll get the police”.

We said, “Yeah, you can get a police. We’re not working. We’re waiting for the police”.

Alright, we went, just take our swag, purlanykarti manayirna roll’m-up-jiniyirni, we shift, other side road crossing. (Ngapi nganapa nyarra yinta palama?) Palanga, palanga camp-jiniyirni, about two mile from the station. We make a camp, pala now.

Waninyiyirni, policeman coming, and one bloke was there, half-caste bloke, Milangka. He coming.

“Purlijimanu there, turlpa nyarra”.

Alright, we went. Yanayirni, finish. Right round yanayirniki pulijimanulu, Marshall. Right round.

“Oh, don’t round me up”.

Purlupurlujarrinyinganakalu, outside now.

“You fellas want this?”.

Muwarrpirni, “You fellas going to come back to work?”.

“No, we’re not working. We’re finishing off”.

“Alright. Well, you want this one?” Put that chain, just payikija mana jayin, jurtirni ngararnaku jayin.

“You fellas want this?”

“It’s up to you”. Palanga finish. Put’m back again. Palanga kurlupirniyinganinyi karajirri now, kukurnjarri-mapulu.

Wurrarnajaninya finish. “All that lot work back”.

Pala nganarna, “What we going to do? Keep going?”

“Well that’s, that’s a kurrngal marrngu. And marrngujakun too. Nyungu walypila nganyjurrumili nyampali. Nyurnungu ngapi marrngu, nganyjurrumili whitefella”.

“Well puru yakurrmalkunya. Puru pala murnurla kulpanyinganyjurrukalu. Kulpanyiyinganyjurrukalu puru”.

Alright. Jinta nganarna wurrarniyirna, “After races, yankulumin. Whitefella wurrarnarnali ngalaya.” Malyurta wurrarnalayirninyi, “After races yankulupulayi. Wiyirr ngarra yankulumin.”

While we were living there they came with calendars for us to begin the strike. We continued working, counting the days by crossing them off on the calendar, day by day. We cattlemen were working separately from the shepherds, we were away working under Bill Shepherd as our boss. The sheep workers were in the west at Pintunya, where the old bald-headed fella was working with a team of marrngu workers. We cattlemen were taken by the whitefella mustering right up close to Braeside, then we made our way back with the cattle to Warrawagine. When we got to Warrawagine we stopped work. We filled up the home paddock with our bullocks, and the others filled up another yard with their sheep. And it was then that we went on strike.

“We’ll go on strike”, I said, “we’ll stay in the camp and talk about it”.

“Yu”, everybody agreed.

The people over in the west [at Sheep Camp] also discussed the matter.

Early in the morning [on the day of the strike] we got up, but not one of us went to get the horses [and put them in the yard, as we usually would]; we wouldn’t let each other go to do this. [The boss] would see that the yard was empty. Instead we went to the meathouse, where we used to camp in the wet season. We made camp there, then went over to the stockyard at the cattle camp to have breakfast.

Then all us marrngu went up to the station homestead to talk to the bosses. The manager, Jim Lewis, and the overseer, Billy Shepherd, came out to meet us. They were our two head stockmen. “Has anybody put the horses in the yard?”

We said, “No, nobody went to get the horses”.

“Oh yeah? What’s wrong?”

“Well, today we’re finishing off”.

That was 1946.

“Ah, who gave you-fellas a hand? Did somebody give you a hand?”

“No, we just made up our minds to stop, because we’ve no home, we camp in the river …

“Ah, yeah? Somebody must have given you a hand”.

“No, we just made up our mind, because we get low wages and rubbish tucker in the woodheap”.

And so that was that. The boss said, “Well, you wait. I’ll get the police”.

We said, “Yeah, you can get the police. We’re not working. We’re waiting for the police”.

So we left them, and went and got our swags. We rolled up our swags, our blankets, and shifted to the other side of the road crossing. (What’s that place called?) We made camp there, about two miles from the homestead.

We stayed there until the policeman came, with a half-caste bloke, a Milangka.

“A policeman’s coming. Get up”.

We went out to meet the policemen, Marshall, and we surrounded him. “Hey, don’t round me up,” he said, backing away. “Do you fellas want this?”

He asked us, “Are you all going to come back to work?”

“No, we’re not working. We’re finishing off”.

“Alright. Well, you want this one?” he asked, tipping chains out of a sack and showing them to us. “You-fellas want this?”

We answered, “It’s up to you”. That was the end of that. He put the chains back again.

The sheep workers over there in the west spoilt things for us. The policeman told us, “all that lot have gone back to work”.

So we wondered, “well, what are we going to do? Shall we keep going?”

“Well there’s a big lot of marrngu over there, and only marrngu too. Over there they’ve got a marrngu boss, but this whitefella is our boss”.

“Well, let’s just give it a go. They’re not coming out on strike with us, they’ve gone back on us”.

Some of us said, “we’ll go after the races”. My brother and I told the whitefellas “after the races, we’ll go. Then we’ll all be gone”.

Citation

Audio: Cranky Iti (Kujupurra), tape 3, recorded by Anne Scrimgeour, Mijijimaya, 25 June 1993, soundfile Kujupurra 16, transcribed and translated by Barbara Hale and Mark Clendon, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library.

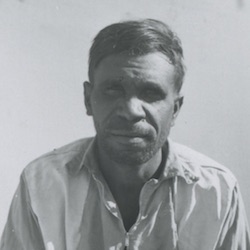

Photo: Cranky Iti (Kujupurra), Board of Anthropological Research, South Australian Museum, AA346/4/22/1 Marble Bar R356.

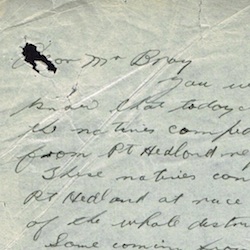

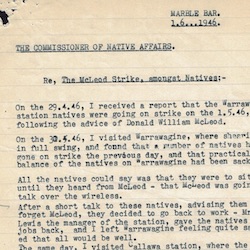

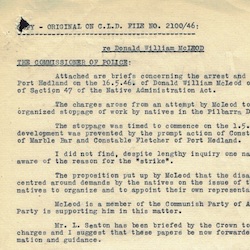

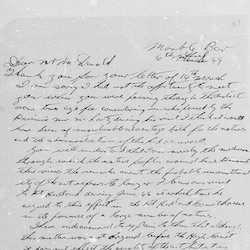

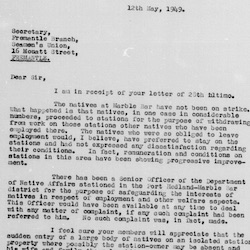

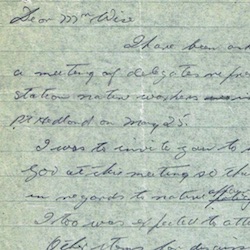

In the wake of this failed action, strike leaders began arranging for representatives from each station to come together for a meeting on 25 May. But, before this meeting could take place, McKenna, Dooley and McLeod were arrested. This letter was written by McLeod from the Port Hedland lock-up.

McLeod Writes from the Port Hedland Lock-Up

Port Hedland Goal

Pt Hedland

22 May 1946

Dear Mr Wise

I have been asked to let you know that that a meeting of delegates representing the majority of station native workers is to be held at the 12 Mile Pt Hedland on May 25.

I was to invite you to have a representative of the gov[ernment] at this meeting so that a statement on Gov[ernment] Policy in regards to native affairs could be considered. I too was expected to attend.

Other items for discussion were

1. Progress made in having Gov[ernment] acknowledge the rights of native workers to organize and appoint their own representative

2. Discuss minimum cash wage of 30/- per week for all native workers

3. Interpretation of Regulation 81 A to C and assurance that regulation would be enforced

4. Right of entry of native reps to all work places to see that the regulations were being complied with

It is unlikely that this meeting will now take place as Clancy and Dooley two organisers have been apprehended and sentenced to 3 months gaol.

Apparently a good deal of pressure has been brought to bear on the natives generally to dissuade them from taking any further action on this matter.

I am myself held in custody awaiting trial on these offences under section 47 and so on.

Your native affairs officials should be in a better position than I am to say if this meeting will take place.

I wish to register a vigorous protest against the action of the police in arresting Clancy, Dooley and myself in connection with this matter, as such action is not in accord with the principles which have been the basis of progress in Aust[ralia]. And on behalf of the native workers demand that a Royal Commission be appointed to enquire thoroughly into and report on [the] application and policing of acts and regulations of the Native Affairs Dept which represent under present conditions a distortion of the original intentions and a grave injustice to the people concerned.

Yours sincerely

D.W. McLeod

Citation

Don McLeod to Frank Wise, 22 May 1946, SROWA, 1945/0800/113-14.

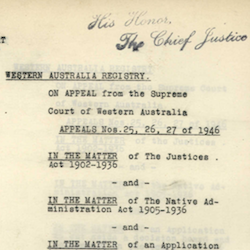

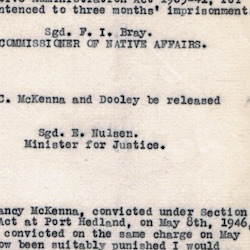

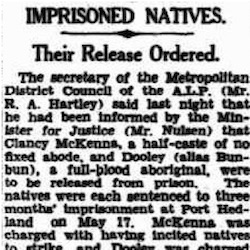

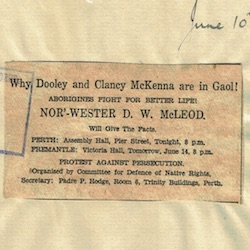

Viewing the strike as a disturbance orchestrated by McLeod, pastoralists hoped he would receive a long jail sentence. They were disappointed when he only received a heavy fine. Following his trial, public pressure led to the early release of Clancy McKenna and Dooley Bin Bin.

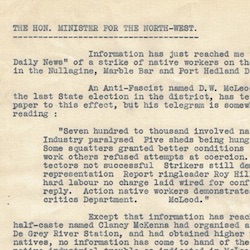

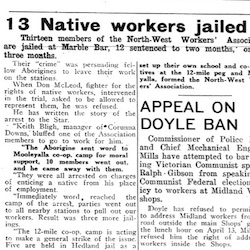

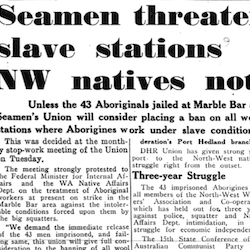

Why Dooley and Clancy McKenna are in Gaol!

Citation

Why Dooley and Clancy McKenna are in Gaol!, SROWA, 1945/0800/178.

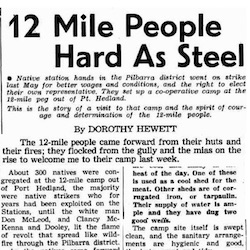

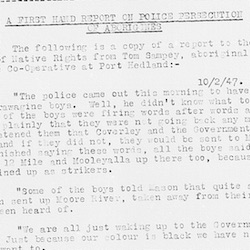

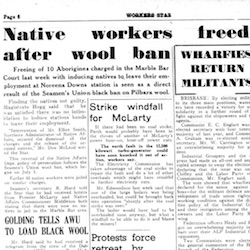

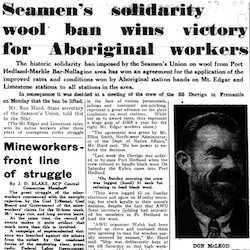

The Workers’ Star drew on information provided by McLeod to report on these events. McLeod probably overestimated the number of people involved in these demonstrations. Police reports suggest that there were about 150 Aboriginal people visiting Port Hedland for the races at that time.

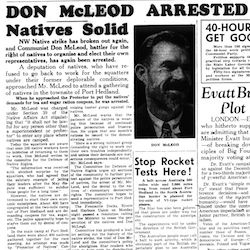

Don McLeod Arrested Again, Natives Solid

Citation

Workers’ Star, 9 August 1946, p. 1, ‘Don McLeod Arrested Again.’

During the second half of 1946, groups and individuals walked off stations and other workplaces to join the strike camps. Caroline Jula, who had worked as a domestic servant at Warrawagine station, joined the strike camp at Moolyella in late 1946.

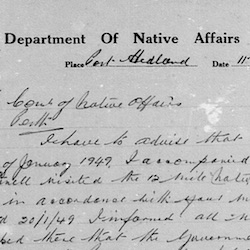

The Western Australian Department of Native Affairs tried repeatedly and persistently to end the strike and return workers to stations. The strikers held out, however, using successful non-violent strategies to maintain their stand.

Caroline Jula, Striking from Warrawagine Station

We bin stop there, and we heard about that strike coming. Hello, old Dooley, he bin coming there.

‘After, you fellas got to strike’.

We strike then, we going to Moolyella. And we bin stop there, right up to Saturday.

We bin tell’m [the station manager] ‘No, we want to go, we gotta follow Don’.

‘We gotta give you little bit tucker, for road’.

‘Na, we got enough, kangaroo, meat’.

Start rolling up swag, that morning, Saturday, we off, and walk, Moolyella. We went walk, right up, have a dinner in the windmill, Three Mile Windmill.

Oh, we gotta billy cans and blankets and all that. Sambo, and wife from Sambo, you know?

Everyone! Everyone. We leave’m Warrawagine, only we leave’m four old people in Warrawagine. We went there, we make a camp in a middle, in a windmill. Boys get a kangaroo, maybe emu, and might be goanna. We finish’m all one day for supper or dinner, we bin finish’m off, oh big mob. We went to Moolyella, strike. One day, when we bin sleep in the middle, in the road, we went, sleep there, morning we went in the road. We have’m dinner there, in the middle, Moolyella. Next morning all the big mob, big mob from Warrawagine. We went there, we see big mob here, all strike. We bin stop there, Moolyella, we bin yandy’m tin, you know, little bit, for tucker, we get tucker little bit, tea and sugar.

Then we bin stop there. They bin make a tucker, get a little bit money, you know?

Citation

Audio: Caroline Jula, tape 1, recorded by Anne Scrimgeour, Woodstock Station, 13 August 1991.

Photo: Caroline Jula, Board of Anthropological Research, South Australian Museum, AA346/4/22/1 Marble Bar R361.

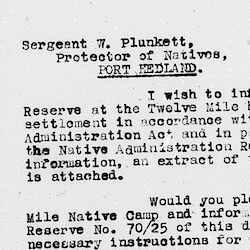

Strikers were increasingly able to negotiate individual agreements with pastoralists to return to station work on increased wages and with improved living conditions, while the Department of Native Affairs found itself unable to reimpose control over marrngu because of fear that those now in employment would re-join the strike. This letter, written by Tommy Sampie in response to a government decision to declare the Twelve Mile a prohibited area for Aboriginal people to camp, caused the prohibition to be quickly reversed and illustrates the considerable political power that marrngu were gaining through their actions.

Aboriginal People Gain Political Power

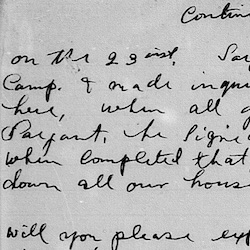

On the 23 inst. Sergeant came out to our camp & made inquiries of all the natives here, when all gathered around or near Sergeant, he signed our names there in. When completed that part he told us to pull down all our houses & humpies.

Will you please explain. I always thought the native affairs would protect us in every way and give us a home in 12 mile after so many of our boys went back to the squatter to work for them, but now you are going to stir the whole thing up over again so dont blame us, because we are fighting for our Rights & our childrens, we must defend our personal rights ourselfs, if not our protectors wont do it for us, we only want our rights & freedom with liberty in our own country.

Now since we were born I can almost say the natives never had a home to live & enjoy himself, never, but since we went on strike, we walked into 12 mile & remained her till last Sunday we heard you our protector was closing our camp. I dont think its fair on your side to do that.

and most of our boys & girls have went back to work for the squatters but now you are causing us more trouble instead of helping us.

five station got working, both men & women working today, and other stations will be notified in time as they are from 12 mile camp went out there, to do some work.

I thought we’d be friend with Government & squatters, but now, we got no one to help us to see we get home for our young children & ourselfs. So we might as well gave all the natives together till you find a way to protect us in a manner that will please every natives of Pilbarra district, our own Government, the Native Affairs never helped us, when we asked them to give us a home, but just went against us & fought for the squatters rights.

If we are going to be shifted by you, where will the squatters get their cheap labors, & another thing, where can we find a home from stations if this camp is closed, so I beg you on behalf of all the Stn boys, guarantee this 12 mile camp to remain intact.

Citation

Tommy Sampie, incomplete letter to Department of Native Affairs, 26 January 1949, SROWA, 1948/0732/86-87.

O’Neill wrote an account of the altercation with Dooley that led to the campaign to fill the jails.

O'Neill's Account of Strikers' Campaign to Fill the Jails

Citation

Laurie O’Neill to Stan Middleton, 29 March 1949, SROWA, 1943/0621/123.

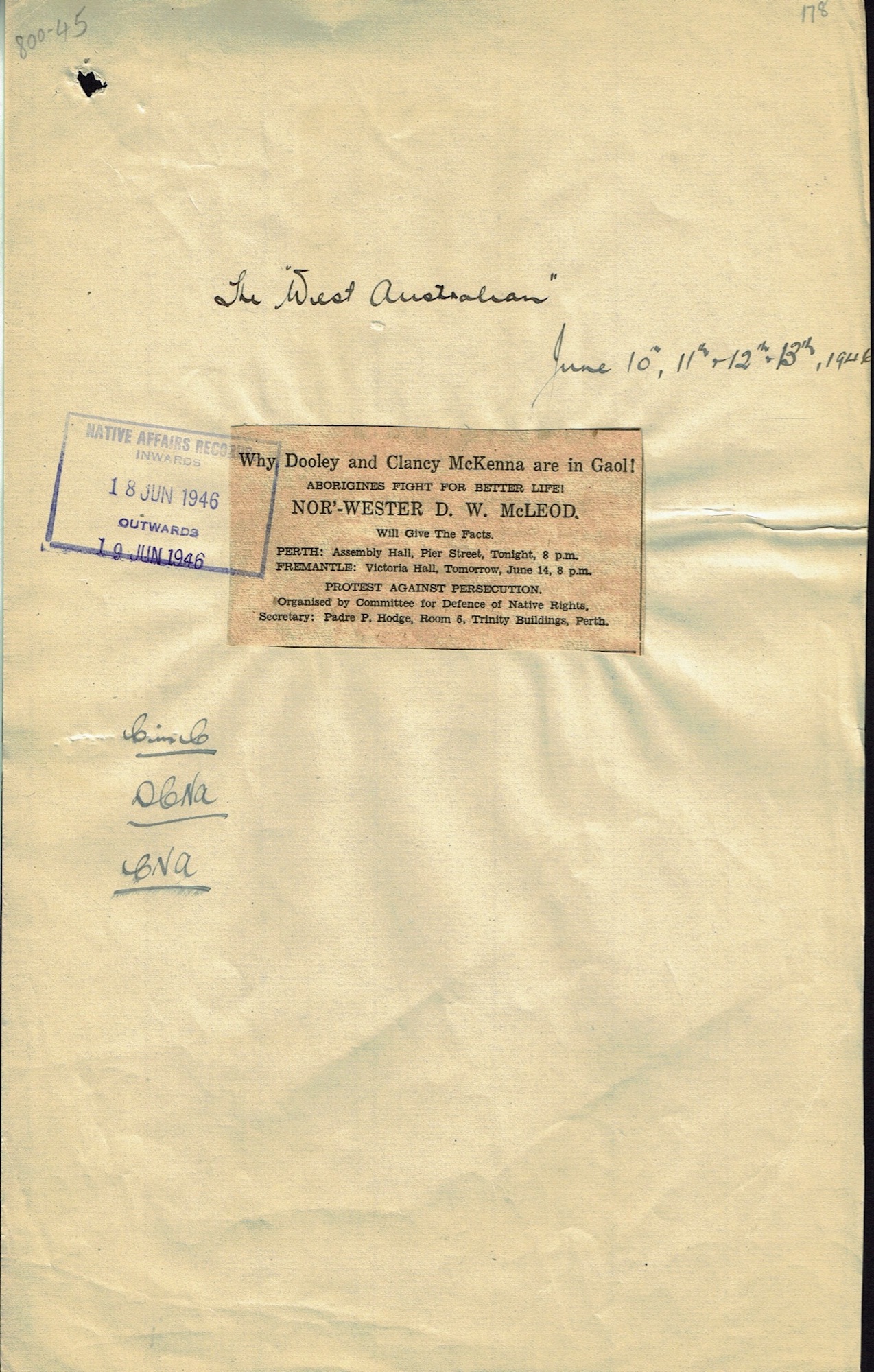

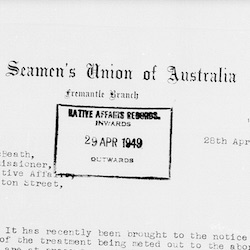

Secretary of the Fremantle Branch of the Seamen’s Union, Ron Hurd, gave the government two months warning before imposing the ban on 1 July 1949.

Seamen's Union Warns Government on Wool Ban

Citation

Ron Hurd to Lew McBeath, 28 April 1949, SROWA, 1943/0621/162.

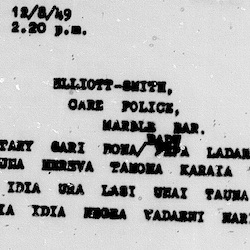

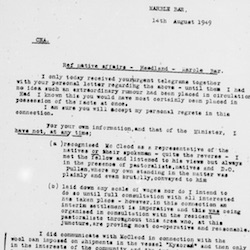

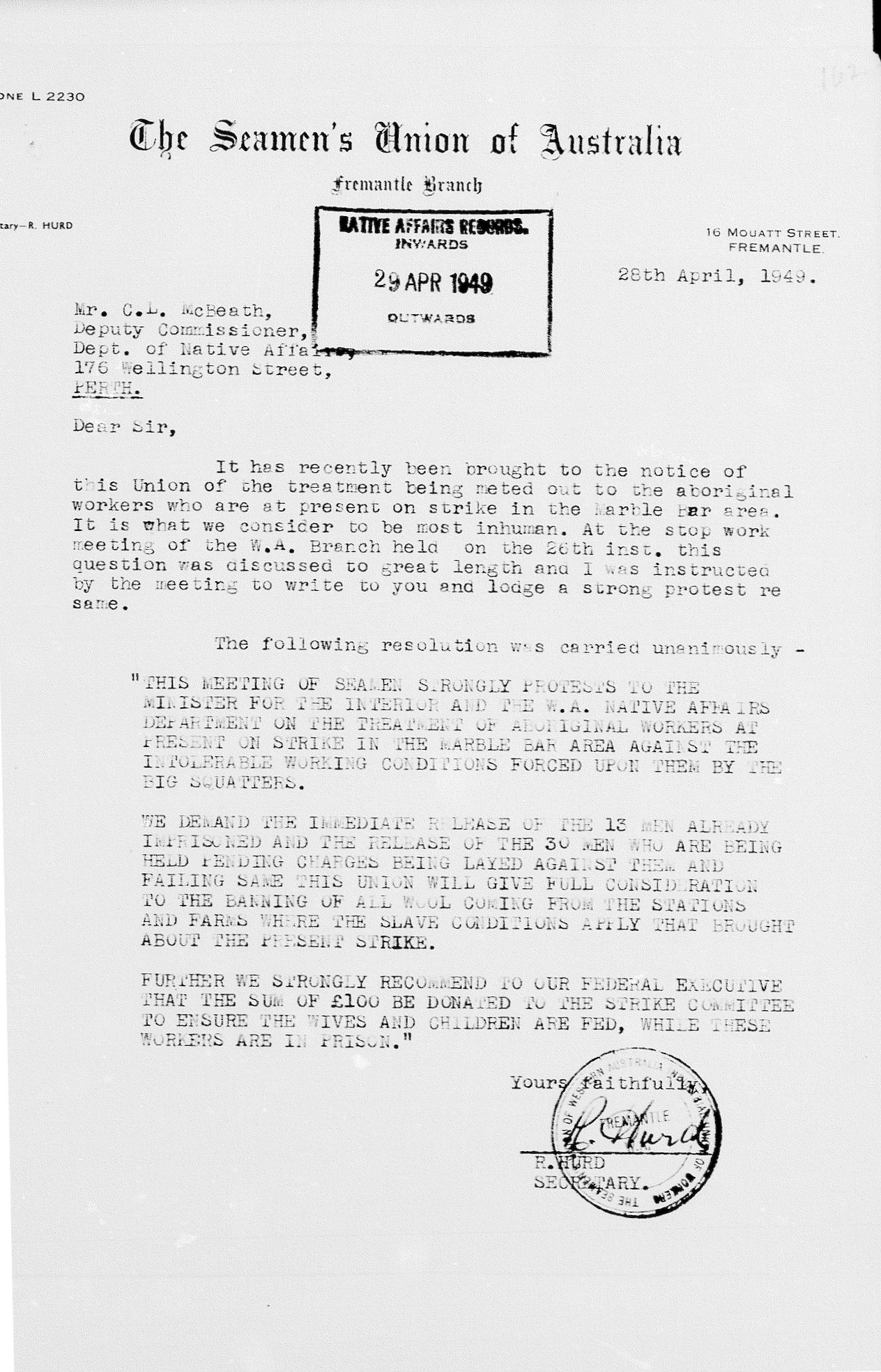

The wool ban was lifted as a result of guarantees made to McLeod by Native Affairs officer Sydney Elliott-Smith, but the Western Australian government bowed to Pastoralists’ Association and the Australian Workers’ Union protests and denied that any agreement had been made. Nevertheless, the strikers’ actions, supported by the Seamen’s Union, led to significant concessions being granted by the Department of Native Affairs.

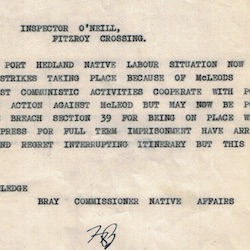

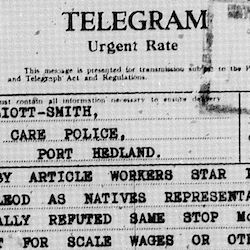

Urgent Telegram on Recognition of McLeod as Aboriginal Representative

Citation

Urgent Telegram on Recognition of McLeod as Aboriginal Representative, Stan Middleton to Sydney Elliot-Smith, 27 July 1949, SROWA, 1949/0454/73.

In the Pilbara, as in other parts of Australia’s north, dependence on Aboriginal labour, including domestic labour, was central to the colonial domination that started after European settlers began to establish sheep and cattle stations in the 1860s. The Aboriginal people were determined to change this system. Speakers of several different languages took part in the strike, including the Ngarla, Nyamal, Nyiyaparli and Kariyarra, who were traditional owners of the country where it took place. Men and women who had migrated into the region from other areas, including speakers of Nyangumarta, Mangarla, Warnman and the Western Desert languages, were also involved.

Beginnings

The Pilbara Aboriginal strike had its beginnings in discussions between a group of men working together building fences and sinking bores on Bonney Downs station near Nullagine in 1944 and 1945. Aboriginal men told a white contractor, Don McLeod, of their dissatisfaction with their lives as low or unpaid workers on the pastoral stations in the area. They spoke of their sense of powerlessness in the face of the pastoralists whose power was bolstered by the police. Since their labour was essential to this economically important industry, McLeod suggested a strike could be effective. But he insisted that the marrngu would need to be well organised.

Snowy Jittermarra, Looking For A Way

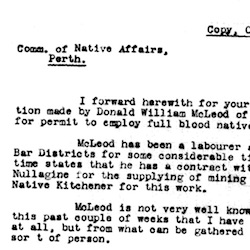

According to Snowy Jittermarra (Maruntu), marrngu had been looking for a long time for a way to acquire greater control over their own lives. Discussions between a Nyiyaparli man called Kitchener and McLeod, who had already come to the attention of authorities for political activities on behalf of Aboriginal people, offered a way forward.

Constable Fletcher's Report on Race-Time Meetings

Ideas discussed included a scheme to obtain land of their own and set up economic enterprises so they would no longer be dependent on station employment. In 1945 marrngu from across the region held meetings to discuss these ideas when they converged on Port Hedland for the annual horse races. Constable Les Fletcher of the Port Hedland police was invited to attend. This is his report of the meeting.

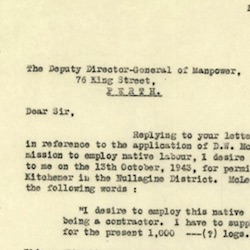

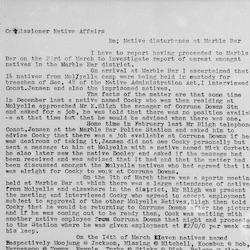

DNA Attempts to Stop Aboriginal Organisers Spreading the Word

The Aboriginal organisers travelled around the area spreading the word about the strike. The Department of Native Affairs was troubled by this and tried to counter it. Nyamal man, Clancy McKenna, was one of the principal organisers. Dooley Binbin, a Nyangumarta man, took up an organising role late in 1945.

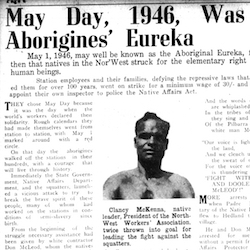

May Day

The initial action, planned for 1 May 1946, was a sit-down strike. On or around that date, Aboriginal people throughout the region refused to work, demanding a basic wage of 30/- a week. They planned to withhold their labour until McLeod had negotiated with the Native Affairs Department to be appointed as an Honorary Inspector of Natives who could address Aboriginal people’s living and working conditions. On some stations, such as De Grey and Strelley, 5/- pay rises were awarded for the duration of the shearing, and this saw the workers return to work. Elsewhere, police officers responded quickly to the strike, travelling around stations to pressure marrngu to return to work. By the end of the first week in May, the only marrngu not working were those evicted from towns and stations for refusing to work.

Cranky Iti, Striking at Warrawagine Station

Small communities of marrngu on widely dispersed stations found it difficult to conduct a strike of this nature. Kujupurra (Cranky) was a cattleman on Warrawagine station on 1 May 1946. He recalls the tactics used by the police to suppress the initial strike action.

McLeod Writes from the Port Hedland Lock-Up

In the wake of this failed action, strike leaders began arranging for representatives from each station to come together for a meeting on 25 May. But, before this meeting could take place, McKenna, Dooley and McLeod were arrested. This letter was written by McLeod from the Port Hedland lock-up.

Why Dooley and Clancy McKenna are in Gaol!

Viewing the strike as a disturbance orchestrated by McLeod, pastoralists hoped he would receive a long jail sentence. They were disappointed when he only received a heavy fine. Following his trial, public pressure led to the early release of Clancy McKenna and Dooley Bin Bin.

The Walk-Off

The opportunity for marrngu to act as a group came in July 1946 when people from across the region attended the annual races in Port Hedland. Marrngu were ordered by the police to camp outside the town, but they defiantly walked into town during the night and set up camp at the Two Mile. This took remarkable courage and was a significant milestone in the development of the strike. Marrngu found that settler power was not absolute after all. Indeed, the police and the Department of Native Affairs were at a loss to know how to respond. When the races ended, marrngu refused to return to stations, setting up two strike camps instead. One camp was established at the Twelve Mile, 20 kilometres from Port Hedland, under the leadership of McKenna, Ernie Mitchell and others, and another at Moolyella, near Marble Bar, under Dooley’s leadership.

Don McLeod Arrested Again, Natives Solid

Before setting up strike camps, the strikers staged a number of non-violent demonstrations in Port Hedland in a show of strength.

Caroline Jula, Striking from Warrawagine Station

During the second half of 1946, groups and individuals walked off stations and other workplaces to join the strike camps. Caroline Jula, who had worked as a domestic servant at Warrawagine station, joined the strike camp at Moolyella in late 1946.

The Western Australian Department of Native Affairs tried repeatedly and persistently to end the strike and return workers to stations. The strikers held out, however, using successful non-violent strategies to maintain their stand.

Aboriginal People Gain Political Power

Strikers were increasingly able to negotiate individual agreements with pastoralists to return to station work on increased wages and with improved living conditions, while the Department of Native Affairs found itself unable to reimpose control over marrngu because of fear that those now in employment would re-join the strike. This letter, written by Tommy Sampie in response to a government decision to declare the Twelve Mile a prohibited area for Aboriginal people to camp, caused the prohibition to be quickly reversed and illustrates the considerable political power that marrngu were gaining through their actions.

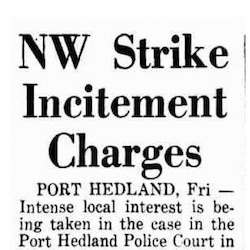

Filling the Jails

Strategies employed by the strikers included acts of civil disobedience in response to heavy-handed policing. In 1949, following the imprisonment of strikers for removing a worker from a station, Native Affairs Inspector Laurie O’Neill threatened further arrests if marrngu continued to assert their own authority. Strikers responded to O’Neill’s warning that there were ‘plenty of police and plenty of jails’ with a defiant campaign to fill the jails. This forced the government to adopt a more respectful and less punitive approach to dealing with the strikers. The campaign to fill the jails also led to union action in support of the strike.

O'Neill's Account of Strikers' Campaign to Fill the Jails

The strikers’ campaign to fill the jails took place in 1949, following the imprisonment of ten men for removing a worker, Cocky Brown, from Corunna Downs Station. In protest, and to demonstrate their refusal to be cowed by O’Neill’s threat, parties of strikers began travelling out to stations to bring more workers into the strike. By April, 43 men had been imprisoned.

Seamen's Union Warns Government on Wool Ban

The imprisonment of so many strikers, and the use of chains in making the arrests, led the Fremantle branch of the Seamen’s Union of Australia to impose a black ban on the shipment of wool from Pilbara stations. Although there was little or no disruption to the wool industry, the ban was not insignificant, adding weight to the actions of the Aboriginal strikers and forcing the Department of Native Affairs to find less punitive responses to the strike. Secretary of the Fremantle Branch of the Seamen’s Union, Ron Hurd, gave the government two months warning before imposing the ban on 1 July 1949.

Urgent Telegram on Recognition of McLeod as Aboriginal Representative

The wool ban was lifted as a result of guarantees made to McLeod by Native Affairs officer Sydney Elliott-Smith, but the Western Australian government bowed to Pastoralists’ Association and the Australian Workers’ Union protests and denied that any agreement had been made. Nevertheless, the strikers’ actions, supported by the Seamen’s Union, led to significant concessions being granted by the Department of Native Affairs.