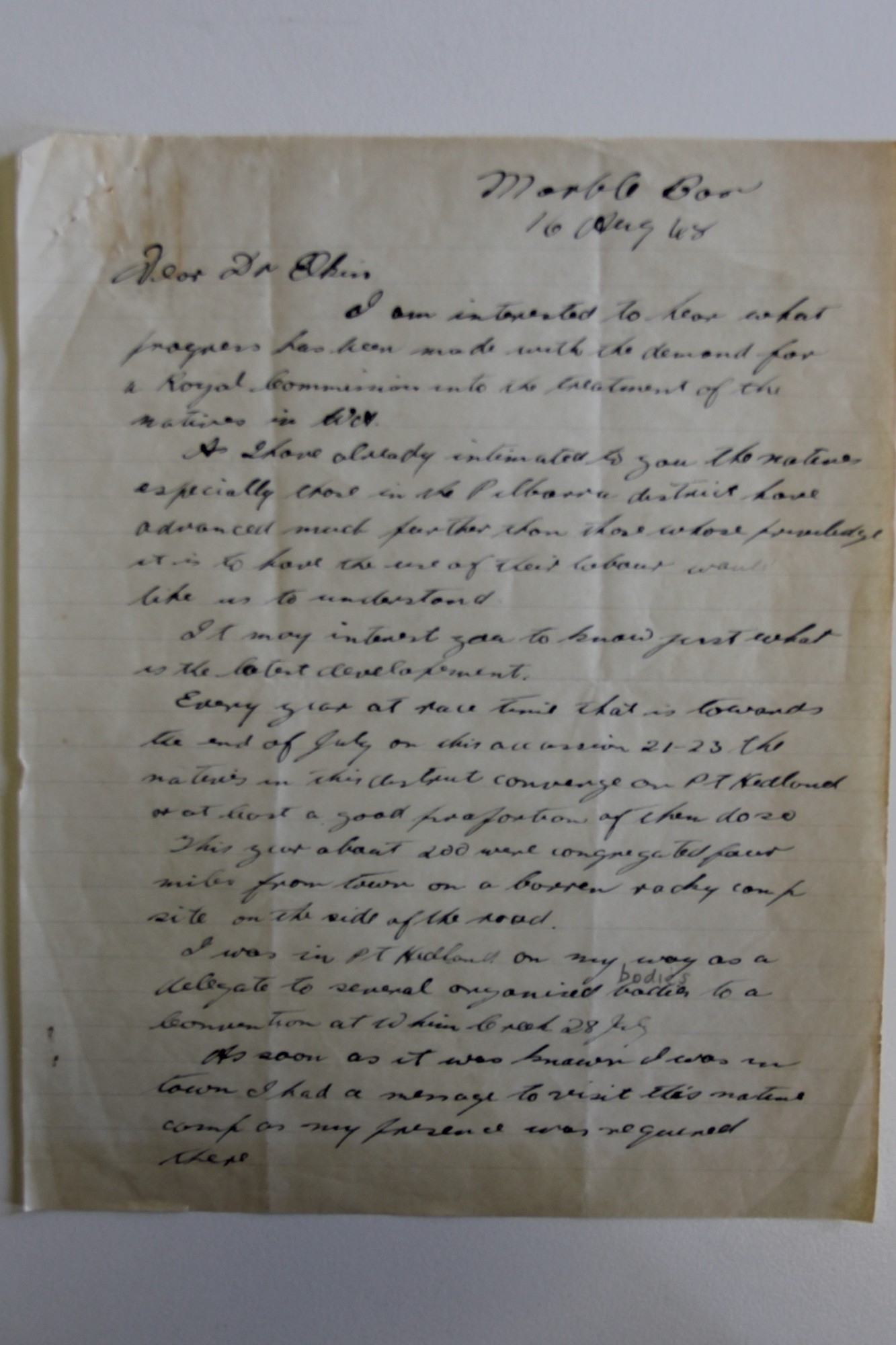

Prior to the strike, Don McLeod apparently wrote voluminous letters to the writer and Australian Communist Party member Katherine Susannah Prichard who lived in Perth (though these do not seem to have survived) as well as long letters to the anthropologist A.P. Elkin on the other side of the continent (which have survived).

Don McLeod Writes to A.P. Elkin

Citation

Excerpt of Don McLeod to Professor A.P. Elkin, 16 August 1945, A.P. Elkin Papers, University of Sydney Archives, MSS P130/12, Box 76, File 262.

A policeman, Les Fletcher, gave this account of the meeting that took place in July 1945.

Aboriginal Storytelling at Race-Time Meeting

Citation

Constable Les Fletcher to Commissioner of Native Affairs Francis Bray, 10 August 1945, SROWA, 1945/0800/13-17.

Once the strike began, a fierce propaganda battle began in which the opposing sides gave highly partial accounts of it in order to win public support: on the one hand, the government and the pastoralists told stories in which they sought to minimise the impact of the strike; on the other, the sympathisers of the strike gave the impression of a highly successful industrial action by the Aboriginal people.

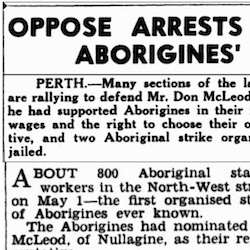

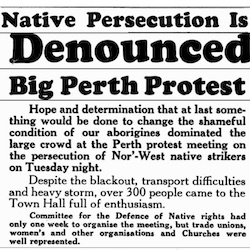

Native Persecution is Denounced: Big Perth Protest

Citation

Workers’ Star, 31 May 1946, ‘Native Persecution is Denounced: Big Perth Protest.’

In McLeod’s telling of the story of the strike, a meeting at Skull Springs in 1942 became a key feature, even though he made no mention of this event in an autobiography he drafted (with the help of a Western Australian historian) in 1955.

Don McLeod, Telling the Story of the Strike

Edited transcript of interview with Don McLeod by Chris Jeffery, 15 November 1978, State Library of Western Australia, OH331, http://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b1822411_4.pdf?download, pp. 16-17, 20-22

DM: Well, they wanted to know what to do and I said, “Well, they couldn’t do anything unless they organised the whole state”. And they said, “Well if we organise the whole state will you show us what to do. Will you, you know, act as our adviser, and will you get control of this fund?” And I said, “Yes, if you can guarantee that you can organise the whole state I’ll certainly show you what to do”, because I didn’t think they could do it, I thought it was too big a job for them. Because any man that pokes his nose into what the squatter was doing to black fellows was looking for trouble. Well, in 1942, which was five years later, [it] would be 1937, when we finished taking the [unintelligible] on the Ashburton, 1942, I was invited to go out to Skull Springs on the Davis River, in the Nullagine district, about two hundred miles east of Nullagine. And I met all the law men from the desert and a lot of other people besides, and we had a meeting there which took six weeks to put through. It was like a United Nations meeting, we had 24 languages, we had sixteen interpreters, and it took us six weeks to work out what we were going to do.

CJ: So, there were 24 different tribes ...

DM: Twenty-four different tribes, the lawmen ...

CJ: … represented.

DM: The whole of the state’s lawmen were there at this meeting. And they give me a crash course in native law and I gave them the way the state had fiddled with their estate and what they were entitled to and what they ought to be entitled to. And what they’d have to do to recover it. And they give me a position in the law above any lawman, in the event — since black fellows take some time to get a consensus — in the event of it needing to take a quick decision, if I took any decision, well then everybody would stick to that, they’d follow then … [End of first excerpt]

CJ: Would you tell me about the strike; how did you organise it?

DM: Well, I never organised it at all. Dooley Binbin and the people organised it, but I was ... They nominated Dooley Binbin at that meeting. If we had to have a strike he was obviously the best man to have, they knew their people, what their capacities were. He wasn’t at the meeting but they nominated him. And we had to pick up a man from the settled portion and the blokes in there picked Clancy McKenna. And these two blokes were given the job of organising the people so that on the first of May they came out on strike.

CJ: How did they get the message through to all these different tribes, to stop work on a certain day?

DM. Oh, well, Dooley Binbin went into a mate of mine in Marble Bar and he got him to give him a calendar, so that he could mark off every day, you know, until come the first of May, which was March, and then that was the date. Well, Dooley, having got that calendar, every time he went to a place he’d do another one and show them how to mark it off, so that when they come to the first of May, that was it. And then he’d go onto the next one, he’d do one there and so forth. So apparently that’s the way he did it. I wasn’t with them, because I couldn’t come within five chain of a congregation of black fellows in those, without written permission. It was worth two hundred pounds, or two years gaol or both. This had to be done in a clandestine manner.

CJ: Were you actually convicted?

DM: Yes, in due course I was up on three counts for that, tempting and persuading natives to leave their legal service. I got ₤96 odd fine or five months gaol. I got an appeal to Privy Council which I’ve never taken up. In the High Court they said that true, that the West Australian blackfellows are virtually slaves. They couldn’t leave the master without permission, they were as tightly tied as any medieval villain or serf to the Lord of the Manor. But, nevertheless, West Australia is a sovereign State, and while those laws applied, they had to be observed and if you breach them, well you have to suffer the consequences. Yet here was a state that got control, had a 70th section, had to provide one per cent of the gross revenue. Now the Act of Native Affairs which replaced the 70th section was called, and a long title, an Act to make provision for the better caring and protection of the West Australian black fellow. In fact, it was a slave act. This is how you can twist words. People who didn’t know any better thought that it was in fact better. But have a look at the Act. You couldn’t work a black fellow except under permit and when he worked under permit he couldn’t leave his legal service without the permission of the boss or the policeman who was his protector. And there was no minimum standard of wages. Now, when I was had up for enticing and persuading natives to leave their legal service on De Grey Station, we cited De Grey as an example. And Laurie O’Neill, the Inspector for Natives, he admitted that the black fellows were living in the creek, like cattle. They had no houses, they had no water supply, they had no sanitation or anything of that nature and they had no minimum standard of wage. They were getting $1.25, but the Commission was satisfied, that’s all they had to do. And that was it. Well, now here it is, they had no minimum standard of wages, they couldn’t leave their legal service, they worked on their own land to make an alien person rich and they couldn’t leave it. If they did they had to get the policeman’s permission or the boss’s permission. Who’s going to give you permission to go if you don’t have to pay wages, bloody ridiculous. And this is an Act to make provision for the better care and protection of Australian Aboriginals. Now there was another section that prevented anybody without written permission to be found within five chains of a congregation of black fellows camped or travelling in pursuance of the native custom. So that by putting that provision between the blacks and the whites nobody could come in contact with [them], nobody knew what the black fellows were doing, they were isolated on the station. So that they were illiterate, isolated and destitute … so that they’d never ever be able to claim what was legally, they were legally entitled to. And this is the so-called native question. It’s nothing to do with the black fellows, it’s all to do with a deliberate organised steal. What we got here is stolen property. We’ve stolen the black fellow’s land, we’ve given him no compensation …

Citation

Excerpts of Don McLeod oral history interview by Chris Jeffrey, 15 November 1978, State Library of Western Australia, OH331.

Accounts told by participants in the strike can enable us to recover aspects of it that are occluded in the contemporary documentary record.

Clancy McKenna Remembers the Strike

Citation

Photo of Clancy McKenna.

In remembering the strike, the strikers dwelled upon certain moments, such as the making of the calendars.

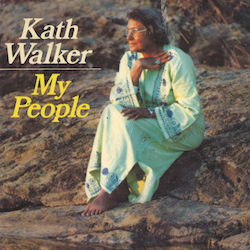

Kangkushot: The Life of Nyamal Lawman Peter Coppin

Citation

Cover of Jolly Read and Peter Coppin, Kangkushot: The Life of Nyamal Lawman Peter Coppin.

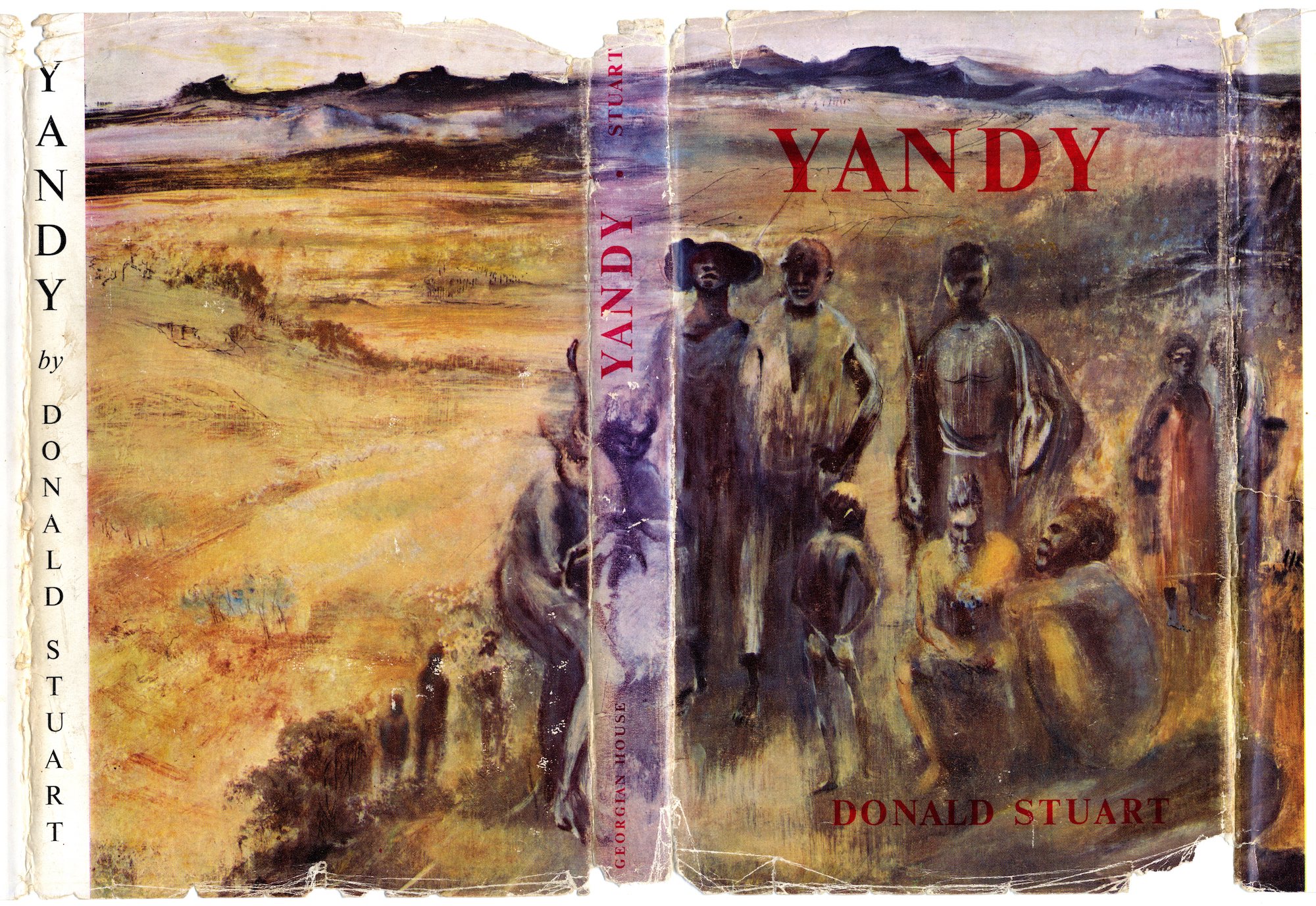

The jacket-cover of Donald Stuart’s documentary novel Yandy featured an oil painting by James Wigley, Don McLeod and his Mob.

Cover of Donald Stuart's Yandy

Citation

Jacket-cover of Donald Stuart, Yandy.

The story of the strike and the cooperative movement won even more attention as Aboriginal land rights and self-determination became popular causes in the early 1970s. Journalists increasingly began to write stories about the strike and the cooperative, more often than not focusing on the role that Don McLeod had played.

McLeod's Mob

Citation

Hamish McDonald, ‘McLeod’s Mob’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 September 1971, p. 20.

Since the 1980s, the marrngu have been more able to ensure that their perspectives are foregrounded in the telling of the story of the strike and the cooperative movement.

Scene from Yandy the Play

Citation

Still photo from Jolly Read, Yandy.

Sculpture of Strike in Public Park

Citation

Photo of the sculpture in the park on Wedge Street.

The strike has been commemorated further afield than the Pilbara, especially by the left. For example, many unions have commemorated the strike in recent years. In 2010 the singer and song-writer Shane Howard recorded a song Clancy & Dooley & Don McLeod that emphasises the support unions lent the strike.

Clancy & Dooley & Don McLeod Song

Citation

Video recording of Shane Howard performing Clancy & Dooley & Don McLeod.

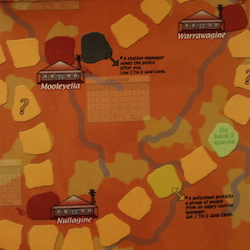

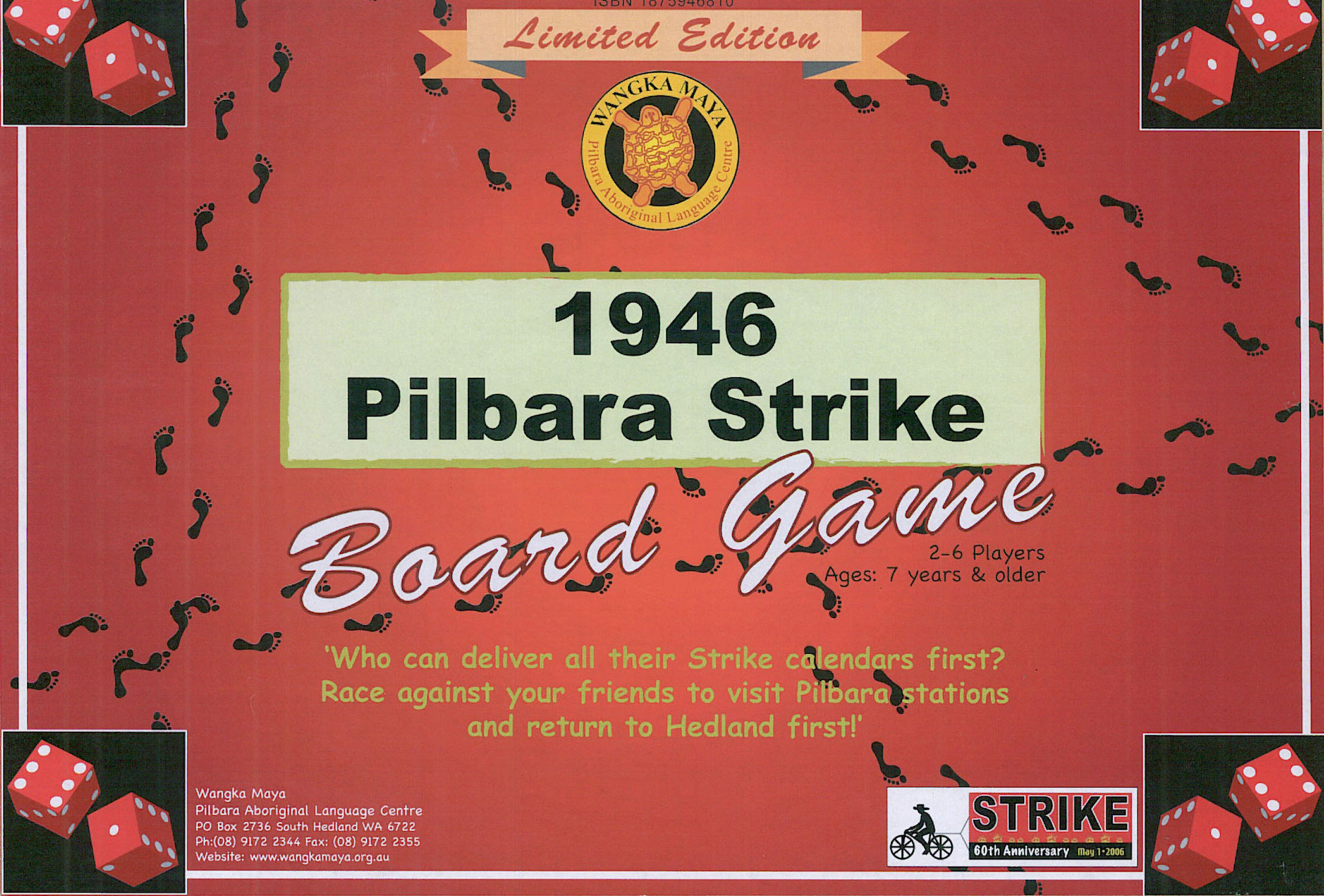

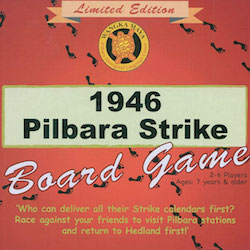

The 1946 Pilbara Strike Board Game Cover

Citation

Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, The 1946 Pilbara Strike Board Game, cover.

The story of the Pilbara strike has been told in many different forms over many years now, and those forms can have a profound influence on its content. Most importantly, the ways in which Aboriginal people represent the past tend to differ markedly from those of scholars working in the discipline of history. Many of the stories Aboriginal people have told about the strike belong to an oral tradition in which the meaning and significance of the event in the present, rather than in the past, is of the utmost importance; and, as the needs of the present have changed, the nature of the stories being told has shifted as well. From a European scholarly point of view, these stories, especially when they are rendered in ways that preserve their original idiom or spirit, are invaluable as they reveal much about the ways in which the past, as it is remembered, has both shaped the marrngu sense of self and informed their actions. At the same time, oral histories, told by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, can shed light on the strike itself, since they reveal aspects of it that are barely evident in the contemporary historical record.

Beginnings

It is often assumed that stories are told only after an event or an experience. But stories are often formulated and told beforehand, thereby making possible the actions they describe. In a political context, telling a story can not only help actors forge a plan for action but also constitute a sense of community among those who will execute it. In the case of the strike, Don McLeod and the principal Aboriginal figures constructed a narrative about the Aboriginal people’s oppression and a struggle to free themselves; they told that story repeatedly to the marrngu; and finally they sought to enact that story together. And, once the strike began, telling the story of what happened and was happening was just as important, since a propaganda battle erupted between the opposing sides.

Don McLeod Writes to A.P. Elkin

Prior to the strike, Don McLeod apparently wrote voluminous letters to the writer and Australian Communist Party member Katherine Susannah Prichard who lived in Perth (though these do not seem to have survived) as well as long letters to the anthropologist A.P. Elkin on the other side of the continent (which have survived).

Aboriginal Storytelling at Race-Time Meeting

But the story-telling that took place among the marrngu themselves was probably even more crucial. One of the most important instances of this took place at a meeting that was held during the Port Hedland races in July 1945.

Native Persecution is Denounced: Big Perth Protest

Once the strike began, a fierce propaganda battle began in which the opposing sides gave highly partial accounts of it in order to win public support: on the one hand, the government and the pastoralists told stories in which they sought to minimise the impact of the strike; on the other, the sympathisers of the strike gave the impression of a highly successful industrial action by the Aboriginal people.

Remembering the Strike

The stories that were told at the time of the strike by the strikers themselves and their supporters have had a profound influence on nearly all of the historical accounts that have been told since. This story-telling has several key features. For example, the strike was first planned at a meeting that took place at Skull Springs in 1942; the strike began on 1 May 1946, and nearly all the people walked off the stations that day; there were simply three leaders: Clancy McKenna, Dooley Binbin and Don McLeod; and the Aboriginal strikers held together as a coherent group and never really returned to the stations as workers. These stories might be regarded as myth rather than history, not least because they were told by the marrngu in a similar manner to the one they used to relate many traditional stories about mythical heroes. And, for those who later founded or supported the cooperative, they provided a charter for future action.

Don McLeod, Telling the Story of the Strike

Throughout his long life, Don McLeod told the story of the strike on numerous occasions and in various forms, including at least three oral history interviews, a draft autobiography, a political tract, and a documentary film.

Clancy McKenna Remembers the Strike

Accounts told by participants in the strike can enable us to recover aspects of it that are occluded in the contemporary documentary record.

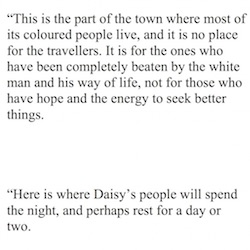

Kangkushot: The Life of Nyamal Lawman Peter Coppin

In remembering the strike, the strikers dwelled upon certain moments, such as the making of the calendars.

History and Legend

Over time, the strike increasingly became the subject of both history and legend, rather than memory alone. In this process, many accounts tended to be influenced more and more by previous tellings of the story. This process can be described as narrative accrual or narrative coalescence. As this occurred, the story of the strike was increasingly told in a way in which particular people and certain events symbolised what happened.

Cover of Donald Stuart's Yandy

The jacket-cover of Donald Stuart’s documentary novel Yandy featured an oil painting by James Wigley, Don McLeod and his Mob.

McLeod's Mob

The story of the strike and the cooperative movement won even more attention as Aboriginal land rights and self-determination became popular causes in the early 1970s. Journalists increasingly began to write stories about the strike and the cooperative, more often than not focusing on the role that Don McLeod had played.

Scene from Yandy the Play

Since the 1980s, the marrngu have been more able to ensure that their perspectives are foregrounded in the telling of the story of the strike and the cooperative movement.

Commemoration

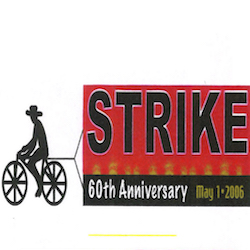

In recent years, the strike has increasingly become the subject of a considerable amount of commemoration, especially at the time of its 50th and 60th anniversaries. This commemorative work has been performed in a broad range of medium.

Sculpture of Strike in Public Park

In 2006 the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, based in Port Hedland, released a DVD called 60 Years Old, which principally comprised an eighteen-minute film, ‘Remembering the 1946 Pilbara Indigenous Pastoral Workers’ Strike’.

Clancy & Dooley & Don McLeod Song

The strike has been commemorated further afield than the Pilbara, especially by the left. For example, many unions have commemorated the strike in recent years. In 2010 the singer and song-writer Shane Howard recorded a song Clancy & Dooley & Don McLeod that emphasises the support unions lent the strike.

The 1946 Pilbara Strike Board Game Cover

In recent years, the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre has produced a range of goods for sale that commemorate the strike.