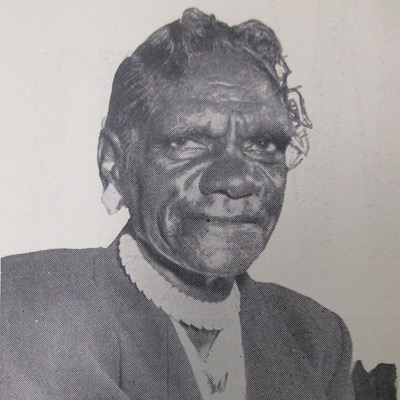

Daisy Bindi

Daisy Bindi was a Nyangumarta woman who became involved in the Pilbara cooperative movement during the 1950s. She did not take part in the strike of 1946-49. Having worked all her life in stock work and domestic service on Pilbara stations, she was an unpaid ‘housegirl’ on Roy Hill Station, to the south of the region, when she heard McLeod and other leaders speak about the cooperative at a meeting in Marble Bar in September 1951. Although the meeting urged station workers to join the cooperative, Daisy decided against leaving Roy Hill at that stage, persuading other workers there to remain at their jobs and negotiate for better wages and conditions, including for women. Wage increases were promised by the management of Roy Hill, but when these improvements were not forthcoming the women refused to work. Although married men were offered an extra 10/- per week as wages for their wives, Daisy insisted that women would not work without direct payment.

When these negotiations failed to secure improvements in their wages, Daisy and her husband, Bindi, visited the NODOM wolfram camp at Blue Bar to investigate the viability of cooperative mining as an alternative to station employment. Impressed by conditions there, Daisy arranged for the cooperative to provide transport to enable everyone to leave Roy Hill. In January 1952, NODOM’s driver, Murphy, and cooperative member Roy MacKay arrived at Roy Hill with a truck and trailer, and almost 100 people from Roy Hill and surrounding stations, including some recent arrivals from the desert, boarded. After receiving medical treatment in Marble Bar, mostly for sore eyes, these people formed an independent mining group under Daisy’s leadership, mining alluvial tin at Cooglegong. A few months later, however, they joined forces with NODOM.

Although Daisy was initially in charge of a work gang made up of the people she brought into the cooperative, her group gradually became dispersed throughout the larger group and she lost her gang-boss status. Like Dooley by that time, she did not have leadership authority within the group but, rather, had the status of a respected senior figure. Visitors to cooperative camps were struck by her strong and dynamic personality, and many of those who met her, including Katharine Susannah Prichard, were inspired to tell her story. She remained with the cooperative through the economic hardships of the 1950s, telling Western Australian author, Bert Vickers, ‘Ah, but it was worth it. My people happy now. We work for ourselves now. Nobody push us around’. A diabetic, she had a leg amputated in 1959, and following the split of 1959-60 she joined the Nomads faction. Daisy died of euremia in 1962.