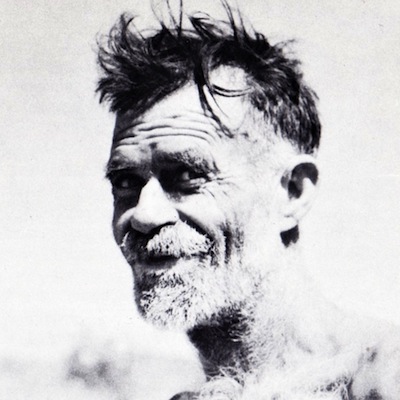

Don McLeod

Born in 1908 in the small Western Australian town of Meekatharra, Donald William McLeod grew up in Geraldton and at the Presentation Convent at Greenough where, he later recalled, ‘they tried to belt Roman Catholicism up my backside with a strap’. He spent his early adult years doing manual work in various parts of Western Australia, sometimes on his own and sometimes with his father. In 1932 he established the Silversheen white asbestos mine in the Ashburton district before shifting north to the Nullagine area in 1939. By 1943, he was working at the Comet Mine near Marble Bar. From late 1943 to early 1946 he worked with his friend Kitchener and two other Aboriginal men on fencing and well-sinking contracts on Bonney Downs station and around Nullagine, engaging in discussions that would lead to the strike.

In later years McLeod would claim to have been drawn unwillingly into the campaign for Aboriginal rights, accepting a task imposed upon him in 1942 by Aboriginal Lawmen from across the state at a large meeting at Skull Springs (Warntilurr) on the Davis River near Nullagine. This claim needs to be treated with caution, however. Oral history evidence indicates that the Skull Springs meeting took place some years later than McLeod claimed, after he had already come to the attention of government authorities for his interest in Aboriginal rights issues. By the time he attended the Skull Springs meeting he had already been actively working to convince marrngu that, although the mainstream legal system was stacked against them, there were legal means by which they could improve their disempowered status and impoverishment.

McLeod’s interest in Aboriginal issues seems to have been stimulated by a number of factors. These include comments about the status of Aboriginal people made by British asbestos dealer Alec Fenton while visiting McLeod’s Silversheen mine in 1937, and friendship with Kitchener some years later. Participation in the Anti-Fascist League during the war fostered an interest in socialism, leading to membership of the Australian Communist Party and awareness of that party’s platform on Aboriginal rights. Protest action taken by Aboriginal people in Port Hedland in 1942 and 1943 also spurred his interest.

During the first two years of the strike, McLeod worked as a labourer on the Port Hedland wharf. His more direct involvement in the economic activities of the strikers began in mid-1948 when he shifted to Marble Bar. Throughout the 1950s, except when business or campaign matters took him to Perth, he lived in cooperative camps with marrngu, not socially integrated into the community but living somewhat apart, often in a tin shed, typing out his interminable correspondence and surviving on little more than damper, tea and cigarettes. Marrngu appreciated his willingness to live with them under the same conditions and on the same diet. Billy Thomas (Pitpit) expressed this in an oral history. ‘He living with the people like how we bin living’, Pitpit said, ‘eating water and bloody meat, water, and some bush tucker, that’s all he bin living. He don’t be like that too, poor fella, no shoes, like that. He starve with us, fight with us, stay with us’.

McLeod had difficult relationships with non-Aboriginal people. Shirley Andrews noted his tendency to consider ‘that everyone who is not 100% with him must be against him’. Supporters found themselves bombarded with letters that frequently turned hostile when their responses did not live up to his expectations. McLeod’s irascible nature was often flavoured by strong personal antagonism that could be directed towards supporters as well as those who held opposing ideological positions. The repeated breakdown of his working relationships with non-Aboriginal people was one of the reasons that he was ousted by marrngu from the leadership of Pindan in 1959.

Following the split in the cooperative in 1959, McLeod continued his involvement with Aboriginal issues through his association with the Nomads (or Strelley) group. Until his death in 1999 he campaigned tireless for Aboriginal self-determination and the restoration of the provisions of Section 70 of the Western Australian Constitution, playing a significant, and today largely unrecognised, role in the movement for Aboriginal rights in Australia.