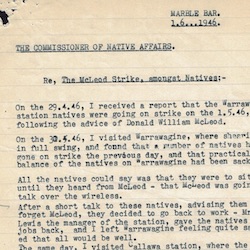

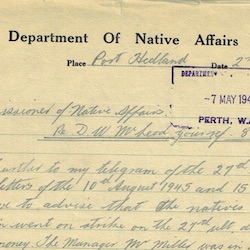

Small communities of marrngu on widely dispersed stations found it difficult to conduct a strike of this nature. Kujupurra (Cranky) was a cattleman on Warrawagine station on 1 May 1946. He recalls the tactics used by the police to suppress the initial strike action.

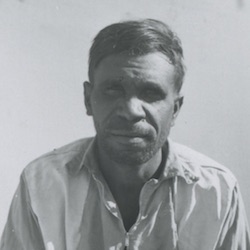

Cranky Iti, Striking at Warrawagine Station

Palanga waninyiyirni pala now yinyapulunganinyi mirlimirli, mirlimirli yinyapulunganinya strike-jarrinyaku. Waninyirni warrkamjarrinyiyirni, number pala day, karrpu pala scratch’m-jinikinyiyirni yamanikinyiyirni. Palaljinikinyiyirni palaljirniyirni. Pulukukarrapa ngurnungu jalpu again, kukurnjari mapulu, nganarna purlikapurluku jalpu again, Bill Sheppard nyampalilu kanganyinganinyi. Ngurnungu karajirri Pintunyanga mirtalu mirtapulkarralu kanganyikinyijaninyi marrngujakun jana. Nganarna whitefella-lu kanganyikinyinganinyi kanyayirni, warrkamjirniyirni purlpi wangkajarrikinyi Braeside-ja, kulpanyakawanikinyiyirni pulukujartiny Warrawagine-karti. Warrawagine-jarrinyiyirni finish. Palanga kalkunikinyiyirnijaninyi puluku puru ngarra home paddock-ngi kanka winya wanikinyinganarnaka. Nyungu janalu kukurnjari yartanga puru kanka again wanikinyijanaka. Yana palanga kuwarringi kuwarringi nyarra, finish. Kuwarringi.

“Ngapijarruluminyi ngurranga, ngurranga wantuluminyi, muwarrpiliminyalu,” wurrarnirna.

“Yu” karramarnayirni everybody.

Ngurnungu karajirri self again muwarrpirniyi.

Yarlipala turlpanyiyirni. Munu yanamayiyirni yawartakartipa. Warliyirninganinyi yawartaku, munu parrjalkulinypa yarta. Yanayirni meathouse, garage, meathouse pala wanikinyi, palanga all the time camping raintime-pa. Palangarra wanikinyiyirni, puralypartu nganayirni, puralypatukarti yanayirni, stockyard ngurnungu, Cattle Camp palanga nganayirni puralypatu.

Marrngulujakun palaja pipurru yanayirni mayakarti. Mayakarti yanayirnijanaku. Tulpanyapulunganaku ngapi, Jim Lewis, he’s the manager, and overseer Billy Sheppard. Palajirri stockmen nganarnamili wurrarniyirni, tulpanyanganaku, “Anybody got a horse in the yard?”

We said, “No, nobody went to get the horses”.

“Ah, what’s wrong?”

“Well, this day we’re finishing off”.

That was 1946.

“Ah, what give you fellas hand? Somebody give you fellas hand?”

“No. We just make up our minds to stop, because we got no home, we camp in the river...”

“Ah, yeah? Might somebody give you a hand?”

“No, we just make up our mind because we get low wages and rubbish tucker, tucker in the woodheap”. Jipi.

Pala finish. “Well, you wait, I’ll get the police”.

We said, “Yeah, you can get a police. We’re not working. We’re waiting for the police”.

Alright, we went, just take our swag, purlanykarti manayirna roll’m-up-jiniyirni, we shift, other side road crossing. (Ngapi nganapa nyarra yinta palama?) Palanga, palanga camp-jiniyirni, about two mile from the station. We make a camp, pala now.

Waninyiyirni, policeman coming, and one bloke was there, half-caste bloke, Milangka. He coming.

“Purlijimanu there, turlpa nyarra”.

Alright, we went. Yanayirni, finish. Right round yanayirniki pulijimanulu, Marshall. Right round.

“Oh, don’t round me up”.

Purlupurlujarrinyinganakalu, outside now.

“You fellas want this?”.

Muwarrpirni, “You fellas going to come back to work?”.

“No, we’re not working. We’re finishing off”.

“Alright. Well, you want this one?” Put that chain, just payikija mana jayin, jurtirni ngararnaku jayin.

“You fellas want this?”

“It’s up to you”. Palanga finish. Put’m back again. Palanga kurlupirniyinganinyi karajirri now, kukurnjarri-mapulu.

Wurrarnajaninya finish. “All that lot work back”.

Pala nganarna, “What we going to do? Keep going?”

“Well that’s, that’s a kurrngal marrngu. And marrngujakun too. Nyungu walypila nganyjurrumili nyampali. Nyurnungu ngapi marrngu, nganyjurrumili whitefella”.

“Well puru yakurrmalkunya. Puru pala murnurla kulpanyinganyjurrukalu. Kulpanyiyinganyjurrukalu puru”.

Alright. Jinta nganarna wurrarniyirna, “After races, yankulumin. Whitefella wurrarnarnali ngalaya.” Malyurta wurrarnalayirninyi, “After races yankulupulayi. Wiyirr ngarra yankulumin.”

While we were living there they came with calendars for us to begin the strike. We continued working, counting the days by crossing them off on the calendar, day by day. We cattlemen were working separately from the shepherds, we were away working under Bill Shepherd as our boss. The sheep workers were in the west at Pintunya, where the old bald-headed fella was working with a team of marrngu workers. We cattlemen were taken by the whitefella mustering right up close to Braeside, then we made our way back with the cattle to Warrawagine. When we got to Warrawagine we stopped work. We filled up the home paddock with our bullocks, and the others filled up another yard with their sheep. And it was then that we went on strike.

“We’ll go on strike”, I said, “we’ll stay in the camp and talk about it”.

“Yu”, everybody agreed.

The people over in the west [at Sheep Camp] also discussed the matter.

Early in the morning [on the day of the strike] we got up, but not one of us went to get the horses [and put them in the yard, as we usually would]; we wouldn’t let each other go to do this. [The boss] would see that the yard was empty. Instead we went to the meathouse, where we used to camp in the wet season. We made camp there, then went over to the stockyard at the cattle camp to have breakfast.

Then all us marrngu went up to the station homestead to talk to the bosses. The manager, Jim Lewis, and the overseer, Billy Shepherd, came out to meet us. They were our two head stockmen. “Has anybody put the horses in the yard?”

We said, “No, nobody went to get the horses”.

“Oh yeah? What’s wrong?”

“Well, today we’re finishing off”.

That was 1946.

“Ah, who gave you-fellas a hand? Did somebody give you a hand?”

“No, we just made up our minds to stop, because we’ve no home, we camp in the river …

“Ah, yeah? Somebody must have given you a hand”.

“No, we just made up our mind, because we get low wages and rubbish tucker in the woodheap”.

And so that was that. The boss said, “Well, you wait. I’ll get the police”.

We said, “Yeah, you can get the police. We’re not working. We’re waiting for the police”.

So we left them, and went and got our swags. We rolled up our swags, our blankets, and shifted to the other side of the road crossing. (What’s that place called?) We made camp there, about two miles from the homestead.

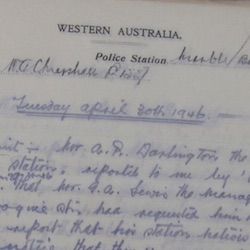

We stayed there until the policeman came, with a half-caste bloke, a Milangka.

“A policeman’s coming. Get up”.

We went out to meet the policemen, Marshall, and we surrounded him. “Hey, don’t round me up,” he said, backing away. “Do you fellas want this?”

He asked us, “Are you all going to come back to work?”

“No, we’re not working. We’re finishing off”.

“Alright. Well, you want this one?” he asked, tipping chains out of a sack and showing them to us. “You-fellas want this?”

We answered, “It’s up to you”. That was the end of that. He put the chains back again.

The sheep workers over there in the west spoilt things for us. The policeman told us, “all that lot have gone back to work”.

So we wondered, “well, what are we going to do? Shall we keep going?”

“Well there’s a big lot of marrngu over there, and only marrngu too. Over there they’ve got a marrngu boss, but this whitefella is our boss”.

“Well, let’s just give it a go. They’re not coming out on strike with us, they’ve gone back on us”.

Some of us said, “we’ll go after the races”. My brother and I told the whitefellas “after the races, we’ll go. Then we’ll all be gone”.

Citation

Audio: Cranky Iti (Kujupurra), tape 3, recorded by Anne Scrimgeour, Mijijimaya, 25 June 1993, soundfile Kujupurra 16, transcribed and translated by Barbara Hale and Mark Clendon, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library.

Photo: Cranky Iti (Kujupurra), Board of Anthropological Research, South Australian Museum, AA346/4/22/1 Marble Bar R356.